Warding off Clinical Validation Denials with Better Documentation

I recently had an epiphany as to a methodology for providers to put “mentation” into their documentation and ward off denials.

By Erica Remer, MD, FACEP, CCDS, ACPA-C

Clinical validation (CV) denials are plaguing us lately. When I work on projects entailing medical record review, I must admit that it is not unusual for me to agree with the payer. However, if a legitimate diagnosis is denied, the blame often stems from the documentation.

I recently had an epiphany as to a methodology for providers to put “mentation” into their documentation and ward off denials.

I recommend a macro in the setting of sepsis. It goes like this:

Sepsis due to (infection) with acute sepsis-related organ dysfunction as evidenced by (organ dysfunction/s).

If the coder can’t identify an infection, either the provider is not documenting it properly (e.g., “decubitus ulcer” is not equivalent to “an infected decubitus ulcer with surrounding cellulitis”), or there is no sepsis. There has to be an infection in order to progress to sepsis.

If the practitioner can’t provide any organ dysfunction in that field, either they missed the organ dysfunction (organ dysfunction is not only SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment), there is no sepsis, and/or there is increased risk of denial.

When I thought about it, I realized that this sentence composition works for lots of conditions, and could be prophylactic against other CV denials:

Acute-on-chronic hypoxic and hypercapnic respiratory failure due to severe exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) as evidenced by oxygen saturation in mid-80s and increased CO2 with pH of 7.32. Placed on BiPAP, steroids, nebulizers, and antibiotics. Will monitor closely.

Pneumonia, probably aspiration, as evidenced by fever, cough, shortness of breath, elevated WBCs, and RLL infiltrate. Was known to have vomited in NH two nights prior. Being treated with antibiotics and supplemental oxygen.

Severe malnutrition due to cachexia from pancreatic CA as evidenced by BMI 14.7, loss of weight of 10 percent in last month, and muscle wasting. Appreciate dietitian consult. Will implement appetite stimulation and dietary supplementation.

The elements of this construction are:

The condition being diagnosed affirmatively or uncertainty (e.g., possible, probably, suspected, likely, etc.);

The etiology, using linkage (e.g., from, due to, caused by, as a result of, etc.);

The manifestations (clinical indicators); laboratory, imaging, or other supporting evidence (e.g., as evidenced by…); and

Plan of treatment.

Maybe they should think about it as: condition…due to…as evidenced by…treated with…

The provider doesn’t need to do this every time they are discussing the diagnosis (i.e., it doesn’t need to be copied and pasted from day to day). It needs to be done upon the initial diagnosis. From that point on, the practitioner just needs to document whatever is relevant that day. Is it getting better? Did some of the manifestations resolve? How is the plan changing? Did the diagnosis evolve from uncertain to definitive? Having multiple mentions of the ongoing condition will demonstrate that it is a clinically valid and significant diagnosis. A best practice is to have it reappear in the discharge summary as well.

Teach this to residents and onboarding providers, and when you are educating service lines on best practice. If you give feedback, use this construction to model good documentation practice.

Some of you might be thinking, “but the payers have specific, ridiculous, unattainable criteria that they demand for the diagnosis of that condition.” That is a different problem. If that is baked into your contracts, address it. If they are just quoting silly criteria to justify unjust denials, fight it. Good documentation doesn’t completely eliminate denials, but it does help the person responsible for appeals, and helps me assess clinical validity when I perform audits.

Have your provider practice good medicine and produce good documentation, expressing what they thought and why they did what they did. It won’t make all denials go away, but it should decrease the number of them. As a bonus, this pattern of construction may help the clinicians organize their thoughts and communicate their thought process to their colleagues.

And that might just improve the quality of care delivered to your patients!

2024 Q1 Coding Clinic Reinforces “As Many Codes as it Takes” Notion

One of the things I have always loved about ICD-10-CM reflects my mantra: “as many codes as it takes.”

By Erica Remer, MD, FACEP, CCDS, ACPA-C

I am overdue to give my comments on the 2024 American Hospital Association (AHA) Coding Clinic published for the first quarter. I really appreciate this Coding Clinic, because it gives reminders of general coding rules.

One of the things I have always loved about ICD-10-CM reflects my mantra: “as many codes as it takes.”

The revisions to the ICD-10-CM Coding Guidelines include the following:

The additions of “other surgical site” for post-procedural and obstetrical surgery in the context of sepsis. This means that there should be at least four codes for sepsis in the setting of a procedure:

A code for the site of infection, specifying the area involved, like superficial or deep incisional surgical site;

The code to specify that there is post-procedural sepsis, T81.44 or O86.04;

A code to identify the infectious agent, if possible;

R65.2- for severe sepsis, because all sepsis is now “the condition formerly known as severe sepsis;” and

And at least one code to detail what the sepsis-related organ dysfunction was.

The answer to a question about how to code “acute prostatitis and cystitis” reminds us that you need both the code for prostatocystitis, which establishes the site, and N41.0, Acute prostatitis, to establish the acuity.

On page 20, the guidance explains that a postprocedural intra-abdominal abscess would take 2 codes – T81.43XA, Infection following a procedure, organ and space surgical site, initial encounter, and K65.1, Peritoneal abscess – to fully flesh it out.

There were several recent questions that arose regarding what “other” or “other specified” codes are meant for conditions for which the provider gives details and often linkage, but with no specific code for the etiology. For instance, chorioamniotic separation goes to O41.8X30, Other specified disorders of amniotic fluid and membranes, third trimester, not applicable or unspecified; and E27.49, Other adrenocortical insufficiency, is one of the codes needed to capture the condition of hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis insufficiency.

A question on page 17 regarding the coding of the verbiage “rheumatoid arthritis with inflammatory polyarthropathy” points out to me that you need to take into consideration where in the classification a code appears. M06.4, Inflammatory polyarthropathy, lives under the umbrella of M06, titled Other rheumatoid arthritis. It probably would have been better if it were titled Inflammatory rheumatoid polyarthropathy. However, I (not Coding Clinic) would also suggest that if the provider had specified “rheumatoid factor positive RA with inflammatory polyarthropathy,” the more accurate code would be M05.79, Rheumatoid arthritis with rheumatoid factor of multiple sites without organ or systems involvement.

There was a set of questions regarding dural tears that I am sure is driving some of you crazy. My experience is that some quality and clinical documentation integrity (CDI) teams try to get their providers to perform contortions to get out of triggering patient safety indicators and complications. They think that the magic words to preclude a complication from being considered a complication are “inherent to” or “integral to.” However, on pages 20 and 21, Coding Clinic is pointing out that regardless of whether the circumstances would have led to a dural tear for anyone performing that procedure, or whether there is thinning, scarring, adhesions, or stenosis, the condition is clinically significant and should be documented and captured as an accidental puncture or laceration. I agree with their assessment.

Pages 23-24 posed an interesting question. A patient presented to the ED with an exacerbation of asthma and did not have access to their albuterol inhaler. Coding Clinic explained that you don’t use an underdosing code for as-needed medications. The code they recommend is Z91.198, Patient’s noncompliance with other medical treatment and regimen for other reason. It makes me think that I might have been using the wrong code for underdosing of antipyretics (to reduce fever). It is still clinically significant and should be recorded (it might be the reason that mom dragged the baby out in the middle of the night – giving too low a dose of acetaminophen), but since it isn’t a long-term drug or prescribed course, like 10 days of antibiotics, it isn’t a “medication regimen.”

There was also a question about transaminitis and hyperbilirubinemia being documented as “acute liver injury due to metastatic liver disease and chemotherapy.” The indexing of “acute liver injury” goes to a trauma code in S36. The coder recognized that this is not correct. Coding Clinic advises using K71.8, Toxic liver disease with other disorders of liver and then codes for the metastasis and adverse effect of the antineoplastic drugs. Since the etiology is known and there is no distinct combination code, K71.8 is indicated, not K71.9, Toxic liver disease, unspecified. The next question also tackles the use of a trauma code – if there is no trauma, you shouldn’t use a trauma code (an S-T code). Medical intervention misadventures are not considered “trauma.”

The next one is a head-scratcher to me. On page 28, a patient with coronary artery disease and a bypass graft (CABG), presents to the ED with chest pain over three days and is diagnosed with a non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), likely from the stenosis of a vein graft. They recommend I24.4, NSTEMI, as the principal diagnosis and I25.10, Atherosclerotic heart disease of native coronary artery without angina pectoris, as the codes. Their reasoning is that “it would be inappropriate to assign a code for angina in the setting of an MI.”

Am I to infer that if the patient hadn’t suffered an MI, you would have used the code indicating “of CAD graft” with “unstable angina pectoris?” What if the patient had chronic stable angina prior to the MI? Are you not allowed to include that information in the coding? I think what they were trying to convey is that the NSTEMI was the progression of the atherosclerosis of autologous vein coronary artery bypass graft with unstable angina, and that once you had the MI, it superseded the CAD in that distribution. In addition, the patient was found to have other CAD, which was not felt to be the etiology of the chest pain.

I know that coding is based on documentation. We want the codes to reflect the conditions the patient has, so if the coding based on documentation doesn’t tell the story accurately, either the documentation or the coding must be adjusted. And…with as many codes as it takes.

As always, I recommend you read the Coding Clinic in its entirety on your own.

Programming Note: Listen live to Dr. Erica Remer as she reports this story during today’s Talk Ten Tuesdays broadcast at 10 a.m. EST.

It Takes Failure to Have Respiratory Failure

I believe I have sorted out why this condition unsettles me and causes us all such grief. I am going to try to lay it out for you all, clinicians, coders, and payers. Please note that I am specifically honing in on adult respiratory failure.

By Erica Remer, MD, FACEP, CCDS, ACPA-C

I have been performing a lot of chart reviews in my consulting capacity, making clinical validation determinations. Whether I am hired by the payor or the provider, I assess the clinical course and documentation and try to make a fair appraisal. One of the conditions that is particularly irksome is acute hypoxic respiratory failure.

For the newly updated pediatric sepsis definition, a survey of practitioners was undertaken to suss out what the consensus was for the medical condition. A scenario was posed, and the respondents weighed in on whether they thought it constituted sepsis or not. I decided to try that approach with acute hypoxic respiratory failure.

I posted this case on LinkedIn:

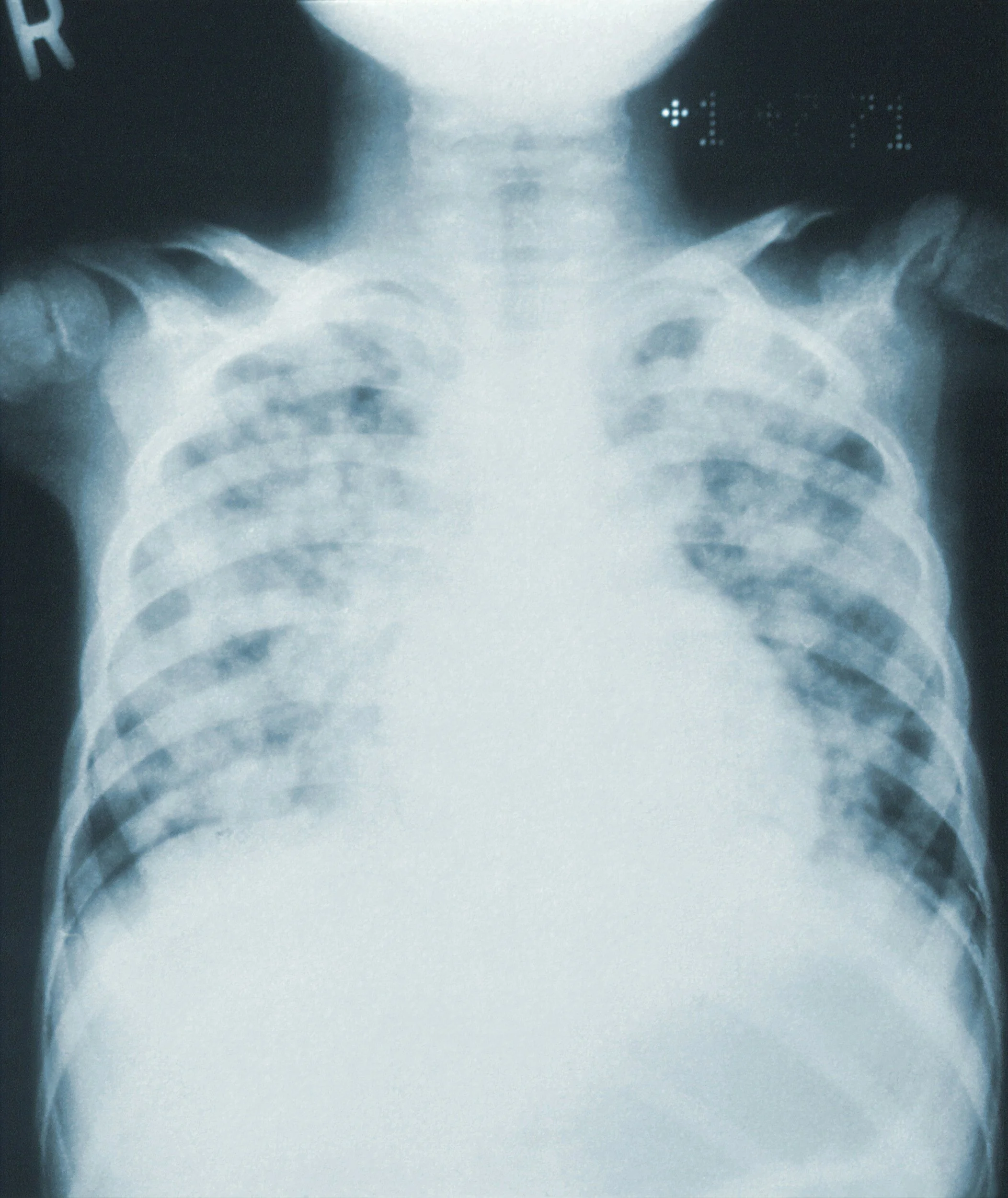

O2 sat of 89 percent on room air. 2L by n/c gets pulse ox to 95 percent. PE: No acute distress. Not toxic appearing. Exacerbation of COPD.

Do you think this is acute hypoxic respiratory failure?

Almost all of those who responded gave me a resounding “no.” A couple of people wanted a little more information, to try to determine if the patient had chronic respiratory failure. One person cited Pinson & Tang’s position that a pO2 < 60 mmHg (SpO2 < 91 percent) on room air was sufficient to conclude hypoxemic respiratory failure.

This highlighted the fact that in clinical documentation integrity (CDI) practice, we often depend on dogma put forth by respected individuals in the field (including me!) We teach our providers and create internal clinical guidelines to support our positions. If there is established evidence-based literature, great! If not, we sometimes fall back on expert opinion. One of the pitfalls of this is we sometimes spurn common sense and rely too heavily on medicine by checkbox.

I believe I have sorted out why this condition unsettles me and causes us all such grief. I am going to try to lay it out for you all, clinicians, coders, and payers. Please note that I am specifically honing in on adult respiratory failure.

The ICD-10-CM code J96.01 is titled “Acute respiratory failure with hypoxia.” Why is it written that way, and not “acute hypoxic respiratory failure?” Let’s deconstruct this.

I posit that first, you need to determine if there is acute respiratory failure.

Acute respiratory failure implies a rapidly developing, severe, and life-threatening impairment of the body to intake or absorb adequate oxygen – or to expel sufficient carbon dioxide. If left untreated, the individual is at high risk of dying from inadequate oxygenation of tissues (e.g., heart or brain) or profound acidosis, which is incompatible with life.

Chronic respiratory failure is more insidious. It often develops more gradually, so the body has time to compensate. The patient learns to deal with shortness of breath if they walk too fast or to stop exerting themselves before ischemia gives them chest pains. If the person comes to equilibrium in chronic respiratory failure, they will have a chronically reduced oxygen level, persistently elevated carbon dioxide level, or both, but their pH will be near-normal. Their status is tenuous, and a new stressor can disrupt the delicate equilibrium, setting off the same life-threatening cascade of events as acute respiratory failure. This is termed acute and (or on) chronic respiratory failure.

The second part of the title is “with hypoxia.” Having a pO2 of < 60 mmHg constitutes hypoxemia, a reduced oxygen level in the bloodstream. Hypoxia is defined by Merriam-Webster as “a deficiency of oxygen reaching the tissues of the body whether due to environmental deficiency or impaired respiratory and circulatory organs.” Hypoxia is the life threat, although it often follows and is heralded by hypoxemia. This is why the code isn’t “with hypoxemia.” Practically speaking, however, we use the terms interchangeably.

In order to have acute hypoxic respiratory failure, you need to have all components: acuity, low oxygen delivery to tissues, and the threat to life.

People are (mis)interpreting Pinson and Tang’s guidance to mean that simply having a pO2 < 60 (SpO2 < 91 percent) or a P/F ratio of less than 300 is adequate to diagnose acute respiratory failure with hypoxia. Even with the caveat that one cannot apply the criteria to patients with chronic respiratory failure, this is not sufficient. This level of oxygen establishes hypoxemia, but more is needed to satisfy the acute respiratory failure piece.

Acute respiratory failure is symptomatic and requires substantial treatment. The symptoms/signs may be pulmonary in nature, like shortness of breath, tachypnea, or intercostal retractions. They may relate to the consequences of the hypoxia or hypercapnia, like anxiety, lethargy, or confusion. These patients typically appear acutely ill.

Treatment is necessary. When I practiced clinically, there were patients on whom I would toss a nasal cannula at a couple of liters per minute. I was trying to make them more comfortable, but I didn’t necessarily think they would succumb without it. Patients in acute respiratory failure need treatment to survive.

For hypoxia, they need significant oxygen supplementation. Most pundits expect to see four or more liters per minute (whatever you consider “high-flow”). A patient does not need to be intubated, but if they are intubated to address air exchange defects (as opposed to “airway protection”), they are in respiratory failure.

Let us remember that when we are reviewing records, we are not assessing the patient directly, but the documentation. It makes it so much easier if the provider produces good documentation to arrive at a valid conclusion. Here are the things I look for:

A history describing development over a short period of time;

Signs or symptoms of respiratory distress (e.g., shortness of breath, tachypnea or bradypnea, air hunger, supraclavicular/intercostal/subcostal retractions, accessory muscle use, abnormal vital signs and/or findings on lung exam) or end-organ dysfunction from hypoxia/hypercapnia (e.g., restlessness, anxiety, reduced level of consciousness, metabolic encephalopathy, diaphoresis, dysrhythmias);

Consistency in documentation;

The history of present illness depicting a patient in distress with symptoms consistent with etiology. Description of baseline status if pertinent;

A general description including some degree of distress, ill-appearing, or in extremis (e.g., “in no acute distress, non-toxic, not ill-appearing” would be inconsistent);

Re-evaluation of the patient’s condition at reasonable intervals;

The declaration of an impression of acute hypoxic respiratory failure at the time (e.g., not days later for the first time, when the patient is no longer exhibiting the signs and symptoms). I expect it to be high on the impression list, not number 9 as an afterthought;

If the diagnosis is prompted by a query, it better be supported with the thought process by the provider. I don’t want to see a random diagnosis just pop up without clinical support and only appear once;

The diagnosis carried throughout the record by all providers. When the condition resolves, it should be resolved in the impression list. It can even be removed if the length of stay is prolonged, but it should reappear in the discharge summary; and

No unresolved conflicting documentation amongst clinicians.

Critical care time being claimed in the ED, the drawing of an arterial blood gas, a pulmonary consult, and/or admission to the ICU are supportive (but not necessary) clinical indicators; and

Treatment suggesting the diagnosis is clinically valid and significant

E.g., high-flow oxygen, CPAP, BiPAP, intubation; and

Aggressive treatment of causative conditions (e.g., antibiotics, pulmonary toilet, steroids, respiratory treatments as indicated).

How about that case? The patient meets criteria for hypoxemia, but is in no acute distress, nor is toxic-appearing. They have a reasonable etiology (COPD), but they only need 2 L/min by nasal cannula. These clinical indicators do not seem to support acute or acute-on-chronic respiratory failure with hypoxia. I would diagnose this as “acute exacerbation of COPD with hypoxemia.” If I were the documenter, I would also have discussed the patient’s baseline to support chronic respiratory failure, if I felt they had it.

Clinicians, if a patient has a life-threatening respiratory issue, think acute or acute-on-chronic respiratory failure. Document the historical and physical points and data that support the diagnosis. Specify whether it is hypoxic, hypercapnic, or both. Be precise and consistent in your documentation. Don’t downplay it or attribute the signs and symptoms solely to alternate diagnoses.

I would recommend linking the acute or A/C respiratory failure to the underlying etiology. I also like linking the manifestations. Detail your thought process and make it hard for the payor to deny the existence of the condition:

Acute-on-chronic hypoxic respiratory failure from pneumonia complicating acute exacerbation of COPD, with pO2 86 percent on baseline home O2 2 L demonstrating air hunger, accessory muscle use, and diffuse wheezing.

If the patient has a low oxygen level, but is not exhibiting signs of respiratory failure, and only requires low-flow oxygen supplementation, call it hypoxia or hypoxemia. If they have acuity, and severity, and require sufficient treatment, call it acute respiratory failure with hypoxia.

Payers do not misinterpret this article and cite that the documentation has to have all of the elements above, or else acute respiratory failure is ruled out. There is always an underlying condition, but there are very few diagnoses in which acute respiratory failure is considered inherent (e.g., acute respiratory distress syndrome, ARDS). Don’t try to gaslight the provider that acute respiratory failure is inherent to pneumonia or heart failure. Clinicians must take in all the facts and data and use their clinical judgment to render a diagnosis.

If you are going to take anything from this article out of context, don’t use it at all!

Physician advisors, bookmark this article and send it to your providers when you discover opportunity in your medical staff’s documentation of respiratory failure. Feel free to condense it and make a tip sheet for them.

Finally, CDI specialists, don’t try to force the provider to use the diagnosis of acute respiratory failure because it is a major comorbid condition or complication (MCC). Our job is to make sure the medical record is accurately depicting how sick and complex the patient is. They need to look as sick in the EHR as they do in real life: no less, but no more.

(For more education on optimal documentation practices, check out Dr. Remer’s Documentation Modules with CME).

Reference: Richard Pinson, Cynthia Tang, Acute Respiratory Failure – All There Is To Know, Pinson & Tang, September 5, 2023.

Navigating the Complexities of Outpatient in a Bed (OPIB)

The implementation of outpatient in a bed (OPIB) classifications in hospital settings presents unique challenges, particularly regarding billing, patient care, and regulatory compliance.

By Tiffany Ferguson, LMSW, CMAC, ACM

The implementation of outpatient in a bed (OPIB) classifications in hospital settings presents unique challenges, particularly regarding billing, patient care, and regulatory compliance. These challenges may vary across hospitals, depending on electronic medical record (EMR) classifications and internal hospital bylaws or policy guidelines for managing this population.

With the looming continued aging of baby boomers requiring more healthcare services and increased social awareness of patient healthcare needs, compounded by provider moral distress, and the administrative pressures of doing more with less, social hospitalizations are continuing to rise.

Understanding and Documenting OPIB

OPIB is defined as an outpatient medical record designation that identifies a patient bedded in the hospital who initially or no longer warrants medically necessary services, from a billing perspective. These patients are often placed in the hospital setting because their social situation leaves them with no other alternative, or they remain in the hospital until an alternative location can be secured, despite the completion of observation services. To date, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has not recognized this level-of-care designation in hospitals.

Since these patients are outpatients, the full admission requirements for hospital inpatients are not required. Thus, documentation requirements should fall to the hospital bylaws and internal policies and procedures.

Extended Observation versus OPIB

It is rare and unusual for a patient receiving observation services to remain in the hospital for a prolonged period. Since observation is a service, the review of medically necessary observation services is either completed, and the patient’s continued stay is due to social considerations, or the patient’s condition warrants hospital admission. For patients who remain purely for custodial reasons, they should be notified that observation services have ended.

There should also be a clear transition documented in the EMR, with an end to the observation services ordered or a change in the EMR encounter type to indicate that observation hours have been completed. This will help avoid confusion regarding any changes or decrease in services due to the patient’s lack of medical necessity.

Key Considerations for OPIB Classification

Defining Outpatient Classification: Clearly define what constitutes an outpatient classification. This involves setting clear criteria and guidelines for when a patient is placed in the hospital for an OPIB designation. Consider incorporating this into the patient classification guidelines to guide the utilization review and physician advisor team in reviewing these patients.

Documentation Requirements: If this designation is a part of your hospital’s EMR, then it will be helpful to ensure that policies and procedures reflect the standards for provider and clinical staff documentation.

Acceptance and Decision Tree: Develop an acceptance or decision tree protocol for determining when a patient qualifies for OPIB. This protocol should outline specific criteria and decision points for healthcare providers to ensure that medical necessity does not exist or has ceased. This decision tree should also include review of alternative locations that may be better-suited for these individuals, rather than the hospital.

Patient Communication: Inform patients about their OPIB classification, including how it affects their care and billing. Clear communication helps manage patient expectations and reduces confusion regarding their treatment plan.

Billing and Ancillary Services: Determine if and how the hospital plans to charge for services rendered to OPIB patients, particularly ancillary/professional services. Establish transparent billing practices to ensure that patients are aware of potential costs. Should the hospital determine that they are not going to bill the patients, it will be key to maintain appropriate reporting (see Dr. Ronald Hirsch’s comments and articles on A2970).

Internal Tracking and Reporting: Implement a system to track OPIB cases internally. This tracking is crucial for future prevention strategies, charity reporting, and maintaining compliance with regulatory standards.

Avoiding Social Admissions

To prevent social admissions, consider leveraging agreements with hospital-owned or community partners. This might include post-acute care facilities, community housing settings, or other properties the hospital owns or partners with. Establishing a fast track from ED to post-acute care may be a lower-cost alternative to taking up medically necessary resources in the hospital (which is likely a whole other article as to why the hospital is not the best fit for social care).

Effectively managing OPIB classifications requires clear definitions, documentation, and proactive communication with patients. Acknowledging the new norm and creating internal guidelines for addressing this population, hospitals can navigate the complexities of OPIB, maintain regulatory compliance, and provide appropriate care while managing resources efficiently.

Properly implemented, these strategies will help avoid legal challenges and improve overall patient satisfaction and outcomes.

NIH Study Finds Link between Treatment-Resistant HTN, SDoH

A recent study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) and funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), has found that adverse economic and social conditions significantly increase the likelihood of developing treatment-resistant hypertension.

By Tiffany Ferguson, LMSW, CMAC, ACM

A recent study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) and funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), has found that adverse economic and social conditions significantly increase the likelihood of developing treatment-resistant hypertension.

Such hypertension is defined as blood pressure that remains above 140/90 mmHg despite optimal use of three antihypertensive medications of different classes, including a diuretic. This condition significantly raises the risk of stroke, coronary heart disease, heart failure, and all-cause mortality.

The study analyzed data from 2,257 Black and 2,774 white adults participating in a larger study that includes over 30,000 Americans. Approximately half of these participants reside in the “Stroke Belt” in the southeastern United States, where stroke mortality rates are higher than the national average.

The social determinants of health (SDoH) factors in the study examined education level, income, social support, health insurance status, and neighborhood conditions. The study identified that several of these factors were linked to an increased risk of developing treatment-resistant hypertension, such as having less than a high-school education, a household income under $35,000, lack of social interactions, absence of someone to provide care during illness, lack of health insurance, residing in a disadvantaged neighborhood, and living in states with poor public health infrastructure.

Over a span of 9.5 years, the study observed that 24 percent of Black adults developed apparent treatment-resistant hypertension, compared to 15.9 percent of white adults. While adverse SDoH increased the risk for both groups, Black adults were disproportionately affected by these adverse conditions, leading to a higher incidence of the condition.

The researchers suggest that addressing the SDoH could mitigate the racial disparities observed and subsequently reduce the higher risks of stroke and heart attack among Black Americans. Effective interventions suggested included improving access to education, increasing household income, enhancing social support networks, expanding health insurance coverage, improving neighborhood conditions, and bolstering public health infrastructure.

In response to these findings, the NINDS Office of Global Health and Health Disparities is developing strategies to promote health equity. In August 2023, a supplement featuring 10 manuscripts was published, providing recommendations for addressing SDoH.

Furthermore, the NINDS’s Mind Your Risks® campaign, launched in 2016, highlights the link between high blood pressure and dementia, particularly targeting Black men ages 28-45. This campaign offers strategies for preventing and managing high blood pressure to improve brain and cardiovascular health.

Although the SDoH risk factors will take more than publications, manuscripts, and educational campaigns to change, this research is significant in acknowledging these disparities for future opportunities of targeted funding to high-risk communities.

Understanding Billing Requirements for Caregiver Training Services

I thought I would revisit these codes with greater specificity, as I am seeing some questions come up related to lack of provider awareness, and some confusion regarding providing support in an individual versus a group setting.

By Tiffany Ferguson, LMSW, CMAC, ACM

As part of the Jan. 1, 2024 Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) guidelines, caregiver training services (CTS) codes were listed as billable services if provided by physicians and non-physician practitioners (NPPs).

I thought I would revisit these codes with greater specificity, as I am seeing some questions come up related to lack of provider awareness, and some confusion regarding providing support in an individual versus a group setting. The intent behind this ruling was to provide practitioners with the opportunity to be reimbursed for their time in providing treatment planning and supporting services to caregivers who support the management of their patients.

Pursuant to the Recognize, Assist, Include, Support, and Engage (RAISE) Family Caregivers Act of 2017, a caregiver is defined as an adult family member or other individual who has a significant relationship with, and who provides a broad range of assistance to, an individual with a chronic or other health condition, disability, or functional limitation. This includes family members, friends, or neighbors who provide unpaid assistance to a person with a chronic illness or disabling condition.

CTS will be reimbursed when provided by qualified practitioners, including but not limited to: physicians, nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists, certified nurse-midwives, physician assistants, clinical psychologists, and therapists (to include physical therapists, occupational therapists, and speech-language pathologists).

CTS is covered for patients under an individualized treatment plan or therapy plan of care, even when the patient is not present. Patient or representative consent is required for the caregiver to receive CTS, and this consent must be documented in the patient’s medical record.

The CPT codes for CTS include the following:

96202: Initial 60 minutes of multiple-family group behavior management/modification training for parent(s)/guardian(s)/caregiver(s) of patients with a mental or physical health diagnosis, administered by a qualified healthcare professional, without the patient present;

96203: Each additional 15 minutes of multiple-family group behavior management/modification training;

97550: Initial 30 minutes of caregiver training in strategies and techniques to facilitate the patient’s functional performance in the home or community;

97551: Each additional 15 minutes of caregiver training; and

97552: Group caregiver training in strategies and techniques to facilitate the patient’s functional performance in the home or community, with multiple sets of caregivers.

It is important to note that the CPT codes are broken down into appropriate group codes or individual codes based on the number of patients represented for caregiver training.

For instance, if the clinician is working with a patient’s daughter who is providing in-home support to her father with dementia, and the clinician and the daughter discuss the diagnosis and regularly review care plan needs and medication concerns to support the patient’s health condition, then CPT codes 97550 would be appropriate. However, if the clinician is hosting a dementia education and support group with caregivers, the code would be 96202.

It is important to note that if multiple caregivers are present for the same patient in the group setting, the time is still the same for the individual patient. Thus, the codes are based on training time related to the patient, not the number of caregivers.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) provides these coding guidelines under Health Equity Services, to support providers for the time they are spending not only to care for patients, but also to support their natural support system. CTS provides holistic support and recognizes the time providers spend talking to family members and caregivers regarding their patients.

Healthcare Coverage Expanded to DACA Recipients

This measure is expected to extend health coverage to approximately 100,000 previously uninsured DACA recipients, addressing a pressing need within the community.

By Tiffany Ferguson, LMSW, CMAC, ACM

In a significant move aimed at enhancing healthcare access for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipients, the Biden-Harris Administration has finalized a rule that expands eligibility for health coverage under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) and Basic Health Program (BHP).

DACA is a program enacted in 2012 that provides relief from deportation and work authorization for immigrants brought to the United States as children. This policy shift, announced by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), represents a step in the right direction toward ensuring equitable healthcare for residents in the United States.

Specifically, the ruling makes a minor but important change to the definition of “lawfully present,” which is a requirement for eligibility enrollment in a qualified health plan. The current definition of “lawfully present” does include certain immigration classifications, such as Green Card holders, Cuban and Haitian entrants, and so many other classifications; however, it specifically excludes DACA. With this modification, DACA recipients will no longer be excluded from that definition, making it possible to participate in the next enrollment period starting Nov. 1, 2024.

It is important to note that the change of definition for eligibility under “lawfully present” does not apply to Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) at this time. The current eligibility for Medicaid and CHIP allows states to include coverage for children and pregnant individuals who are lawfully residing in the United States, including those within their first five years of having certain legal status.

To fill the gap, the PPACA will allow noncitizens who are ineligible for Medicaid because of their immigration status to access financial assistance, such as the Premium Tax Credits and Cost Sharing Reductions through a Marketplace plan, even if their income is below 100 percent of the federal poverty level.

This measure is expected to extend health coverage to approximately 100,000 previously uninsured DACA recipients, addressing a pressing need within the community. The news briefing on this change from CMS stresses the belief that healthcare coverage is a right, not a privilege.

CMS expressed a commitment to providing comprehensive education and technical assistance to support the implementation of this rule, ensuring that immigrants and other communities receive the necessary guidance to navigate the healthcare enrollment process effectively.

CMMI Independence at Home Program Falling Short After 8 Years

In late April the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation Center (CMMI) released the evaluation of their Year 8 Independence at Home (IAH) demonstration.

By Tiffany Ferguson, LMSW, CMAC, ACM

In late April the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation Center (CMMI) released the evaluation of their Year 8 Independence at Home (IAH) demonstration. IAH is a Congressionally mandated initiative that seeks to evaluate the efficacy of incentivizing home-based primary care, reducing healthcare spending, and enhancing the quality of care for high-cost, high-need Medicare beneficiaries. This evaluation has provided valuable insights into the impact of such interventions, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The IAH initiative commenced in 2012 with 18 participating practices, aimed at testing whether payment incentives could drive improvements in healthcare outcomes. Over subsequent years, the number of participating practices decreased, with only seven practices remaining by Year 8, amid the challenges posed by the pandemic for in-home services.

Some of the decline in participating primary care clinics is attributed to the program’s strict requirements, such as being available for primary care home visits at all hours, pending patient need, and the requirement to achieve success in cost reduction at least once in three consecutive years. The beneficiary requirements include that Medicare Fee-for-Service (FFS) patients have at least two chronic conditions, require assistance with at least two activities of daily living, and have been hospitalized and received acute or subacute rehabilitation services in the 12 months prior to program enrollment. Beneficiaries must also not be in any long-term care or hospice program at the time of enrollment in the demonstration.

The evaluation focused on assessing the effects of IAH on total Medicare spending per beneficiary per month (PBPM) and other relevant outcomes, such as the number of ambulatory visits compared to acute-care services the members received during the demonstration period. In Year 8, although there was a potential reduction in total Medicare spending, it was not statistically significant. Notably, the incentive payments made to IAH practices exceeded the estimated spending reduction, raising questions about the cost-effectiveness of the program.

The report noted that while IAH beneficiaries experienced 16 percent more ambulatory visits compared to their counterparts, primary care remained the central service to their healthcare delivery needs. The breakdown of results was mixed: although inpatient spending was down, hospital admissions increased in Year 8, as did readmissions.

The findings suggest that while the IAH initiative may seem theoretically appropriate to enhance the patient-PCP relationship, the sole mechanism of home-based services did not yield significant results (and likely was near-impossible during the pandemic). In addition, this is likely difficult to scale, given the already known shortage of primary care physicians and the efficiencies that telemedicine can provide, which are outside model expectations.

Additionally, the role of extenders to support home-based services such as chronic care management and community health workers may be better-suited to address in-home care for patients with chronic conditions and in need of home assistance than pulling primary care providers out of the clinic for home-based services.

In conclusion, this model makes splitting the value-based and FFS payment structures difficult, as program design was incentivizing services on top of a FFS reimbursement structure, rather than a replacement via other capitation or value-based payment methodologies.

Coding Questions Arising From NPAC, Answered

My philosophy always has been to encourage providers to deliver excellent medical care, foster excellent documentation, have CDI specialists (CDISs) pick up the slack when needed, and ensure that coders accurately and compliantly code – and your reimbursement and quality metrics will fall where they belong in every model.

By Erica Remer, MD, FACEP, CCDS, ACPA-C

I attended the 2024 National Physician Advisor Conference (NPAC) hosted by the American College of Physician Advisors (ACPA) in the middle of April. Its theme was “Safeguarding Patients Amidst Shifting Currents of Healthcare.” I love this conference because it is so rich with information and expands my knowledge base beyond clinical documentation integrity (CDI).

I gave an intro to CDI talk at the Essentials and Fundamental course on the first day, where we trained new physician advisors (PAs) and prepared veterans to sit for the ACPA-C. This is a new certification developed by the premier physician advisor organization to signify that an individual has the working knowledge to serve as a PA.

I also had the honor of kicking off the second day with a plenary session called Physician Advisors: Lifeguards Innovating Solutions to Diverse CDI Problems, in which I shared some details about projects I implemented while I was a physician advisor. I received some questions after the fact, and thought this might be a good venue in which to answer them.

How can you get organizations to move beyond only using MS-DRGs as the tool of risk-adjusting metrics?

Originally, CDI was meant to seek out and capture comorbid conditions and complications (CCs) and major CCs (MCCs), thus optimizing each MS-DRG and tier and improving reimbursement and length of stay. When the All-Patient Refined (APR)-DRG methodology was introduced, optimizing the severity of illness (SOI) and risk of mortality (ROM) metrics was a companion goal.

Then came value-based purchasing and other related quality metrics, again establishing other risk-adjustment-type models. And we can’t forget the Hierarchical Condition Categories (HCC) model for Medicare Advantage (MA) and other Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs).

If an organization is only looking at MS-DRGs, they are missing opportunities in multiple other risk-adjusted models. It’s a good place to start for burgeoning CDI programs, but it is only a jumping-off point.

My philosophy always has been to encourage providers to deliver excellent medical care, foster excellent documentation, have CDI specialists (CDISs) pick up the slack when needed, and ensure that coders accurately and compliantly code – and your reimbursement and quality metrics will fall where they belong in every model.

This segues into another question asking if I have any comment on documentation for getting out of PSIs (patient safety indicators). I attended two great talks on the topic of PSIs and quality metrics, by my Vice Chairs (Waldo Herrera-Novey and Adriane Martin) and two other members of my committee (Neelima Divakaran and Joey Cristiano). We all agree: We want folks not to get dinged when the problem is not really a post-procedural condition, and to address medical quality issues if it is. I never condone doing excessive contortions to avoid legitimate post-operative complications. Providers need to be taught that post-op is not a temporal reference, and to ensure that proper linkage is present. If the acute hypoxic respiratory failure is due to an exacerbation of underlying chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), say that, not “post-operative respiratory failure.”

Another PA asked if I could suggest resources through which you can access how CC/MCCs have financial impact on reimbursement. MS-DRGs are tiered by whether there are CCs or MCCs. Having a single CC is equal to having five of them. The relative weight is a measure of the average resource consumption, severity, and complexity of the patient. When you multiply the relative weight by the hospital’s blended base rate, you determine the reimbursement. If you refer to Table 5 of the current fiscal year’s Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) Final Rule (https://www.cms.gov/medicare/payment/prospective-payment-systems/acute-inpatient-pps/fy-2024-ipps-final-rule-home-page), you can find the specific DRGs’ relative weights. You can see the difference between a base DRG without a CC or MCC versus with one. You have to ask your administration for your hospital’s base rate.

Our health system has chosen to use Sepsis-2 as our criteria. Are we wrong? and Why not use severe sepsis if it’s on the list of CMS-approved codes and there’s a recognized definition?

First, let me get the terminology straight. SEP-1 is the terminology that indicates The Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock Management Bundle, which is the National Quality Forum sepsis quality measure that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) use. Its aim is to standardize sepsis treatment to reduce morbidity and mortality from the condition.

(To find the most up-to-date version, search for Specifications Manual for National Hospital Inpatient Quality Measures and the year of interest. It is listed by quarter. For Q3 and Q4 2024: https://qualitynet.cms.gov/files/65972a96d4b704001df0ae89?filename=HIQR_SpecsMan_v5.16.zip)

In the 1990s, esteemed medical groups came together to try to define the condition of sepsis and operationalize its treatment. Multiple iterations of the literature came out every few years, but Sepsis-2 (not SEP-2) was essentially defined as a presumed or confirmed infection with some systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria. Although there were always other clinical indicators that could be seen in sepsis, the medical community gravitated towards using the general SIRS criteria, which were ubiquitously collected in all patients in whom the diagnosis was being considered. These were:

Fever or hypothermia;

Tachycardia;

Tachypnea; and

Elevated or low white blood cell count.

In Sepsis-2, there were three buckets of sepsis: sepsis as defined above, severe sepsis, which was sepsis with organ dysfunction, and septic shock, which was severe sepsis with hypotension not reversed with fluid resuscitation. ICD-10-CM has codes to indicate all three gradations.

Eventually, it was recognized that this was too broad a definition – there were many patients with infections who exhibited SIRS criteria but did not have sepsis, and some patients who had sepsis but didn’t demonstrate these particular signs.

Hence Sepsis-3. In 2016, The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) were rolled out. The definition was established as “life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection.” It was recognized that SIRS was sometimes an appropriate response to infection, and therefore, might not indicate sepsis. Furthermore, the presence of organ dysfunction is the critical ingredient for the diagnosis of sepsis.

This contracted the buckets to two: sepsis (the condition formerly known as severe sepsis, which includes organ dysfunction) and septic shock. ICD-10-CM did not change the coding schema. As a result, all sepsis now should have a code for the sepsis, another code indicating the presence of organ dysfunction, with or without shock, and additional codes for the causative infection and the resultant organ dysfunction.

In early 2017, Surviving Sepsis Campaign adopted the Sepsis-3 definition. They concurred with the International Consensus folks that “The current use of two or more SIRS criteria to identify sepsis was unanimously considered by the task force to be unhelpful” because “SIRS criteria do not necessarily indicate a dysregulated, life-threatening response.”

During the reign of Sepsis-2, many organizations put in place an alert system, and they utilized those basic SIRS components as the trigger. It is still useful as a warning signal, but SIRS does not establish sepsis. Many providers are resistant to change and cling to SIRS. I am supportive of using SIRS to identify patients who might have sepsis, but I strongly caution against using it as the diagnostic criteria.

The question I would ask the first organization is: do they want to catch in their net patients who do not end up having sepsis? Identify potential sepsis patients preliminarily and then have the clinicians rule it out over the course of the encounter. Then, the diagnosis should be removed before being coded and final-billed.

If you don’t, you frontload the system with patients who are erroneously assigned into a sepsis DRG, and you will be inundated with clinical validation denials on the back end. Not only that, but the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) has added Medicare inpatient hospital billing for sepsis to their workplan.

Is it wrong to use Sepsis-2 as your criteria? I would not recommend it. The current definition has been around for seven years. It’s time to transition.

Why shouldn’t providers use “severe sepsis” if it is on the list of CMS-approved codes and there’s a recognized definition? I don’t believe clinicians should alter their practice of medicine to satisfy coding. They may need to include some antiquated terminology, however, for the coders to capture legitimate conditions, due to the peculiarities of coding rules. Fortunately, there is coding guidance instructing coders that if providers diagnose sepsis with related organ dysfunction, the coder may compliantly pick up R65.20, Severe sepsis without septic shock, without the doctor using the obsolete qualifier “severe.” The condition formerly known as “severe sepsis” is now just “sepsis.”

Consider inserting my macro into your electronic health record (EHR):

Sepsis due to (infection) with acute sepsis-related organ dysfunction, as evidenced by (organ dysfunction/s).

This allows the clinician to avoid having to use old terminology, with the bonus of helping them ensure that the condition is indeed present and clinically valid.

The last question was, “How do you message the importance of thorough and complete documentation when physicians/providers are thinking the E&M 2023 changes have now relieved them of ‘note bloat?’”

I don’t endorse conveying the message that documentation is for billing. I believe thorough and complete documentation is important to tell the story of each patient encounter.

The professional fee Evaluation and Management (E&M) changes made in 2023, when Inpatient and Observation Hospital Care merged, are only based on medical decision-making (MDM) or time, which now should reduce note bloat. The history and physical examination should be performed and documented “as medically appropriate.” No more gratuitous review of systems just to check a billing box. There is no reason to embed a radiology report in the progress note at all, let alone every day of the admission. The provider only gets credit for it once. Rather than copying and pasting the assessment and plan daily, maybe spend a few moments thinking about what needs to be in the note today and how it informed your decisions.

Reducing note bloat means streamlining the documentation to make it really count. Does “no acute events overnight, no acute distress this morning, reportedly at baseline” explain why the patient in Room 204 is still here today? Does a list of signs and symptoms relay what your impression is? Does a hodgepodge of copied and pasted paragraphs really constitute a discharge summary? Remember that your “copying and pasting saves me time” is someone else’s “I hate slogging through other people’s copying and pasting to find the essential points.”

It is crucial to not buy into the “documentation is an unwanted burden on the provider” nonsense. Documentation is part of the process of delivering quality medical care to the patient and enabling others to recognize it. If providers put “mentation” into their documentation, the medical record and the patient will be better off for it.

Who Can Perform Clinical Validation?

Providers shouldn’t be able to engage in fraud and abuse, and payors should have to pay for services legitimately rendered without throwing up roadblocks.

By Erica Remer, MD, FACEP, CCDS, ACPA-C

There has been a kerfuffle on LinkedIn I would like to expound upon today. A colleague of mine, Siraj Khatib, was recently expressing his exasperation at clinical validation audits.

He referred to the Recovery Audit Program Statement of Work (SOW). In 2011, there was a paragraph in the section titled DRG Validation vs. Clinical Validation, which read, “clinical validation is a separate process, which involves a clinical review of the case to see whether or not the patient truly possesses the conditions that were documented. Clinical validation is beyond the scope of DRG (coding) validation, and the skills of a certified coder. This type of review can only be performed by a clinician or may be performed by a clinician with approved coding credentials.”

Dr. Khatib went on to posit that “only a bedside clinician is able to understand, interpret, (and) judge a patient’s clinical condition,” and pondered how “a medical director can have clinical acumen … (having) relinquished bedside medical practice for the comfort of an office, awaiting a bonus to churn out denials.”

There is a lot to unpack here.

First, I would like to validate the frustration of incurring unfounded denials. It requires a great deal of time, effort, and money to combat denials. Sometimes, there is legitimacy – the medicine is questionable, or the documentation is weak. Often, it is infuriating – the medicine is solid, the documentation impeccable, and the insurer is just throwing spaghetti against the wall to see what sticks.

Who is qualified to perform clinical validation, determining if a patient possesses a condition that is documented? The only one who truly can perform clinical validation is a clinician who is taking care of the patient. Did the patient have an exacerbation of their chronic systolic heart failure or not?

However, that is not how the system works. People who are not responsible for the patient’s medical care review the documentation and must make determinations based on the way the encounter is portrayed in the medical record. That is referred to as “clinical validation.”

Who is sufficiently competent to perform this role? The 2011 SOW expressed the decision of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) that they were going to only permit clinicians to make clinical validation determinations. I have always asserted that their decision to only utilize clinicians, such as nurses or physicians, is not a universal mandate. It was the stated practice of CMS.

Two of the best clinical documentation integrity specialists (CDISs) I have ever known were non-clinicians, and came from the health information management (HIM) world (you know who you are, Colleen and Kathy!) I do not think it is out of the question that someone from HIM would be capable of doing clinical validation, but I do contend that not all HIM individuals would be able to do so. They need to have experience in the clinical setting and long-term exposure to the medical record. Although clinicians (e.g., nurses, advanced practice practitioners, foreign medical graduates, etc.) are more commonly employed as CDISs, knowledgeable HIM folks are allowed to be CDISs. If they can serve as a CDIS, they can perform the task of clinical validation.

Institutions and systems can make the determination as to whom they deem competent to perform clinical validation. They do not need to insist on clinician credentials. By the same token, commercial payors have the latitude to make this same decision for their organization.

I completely missed the memo about this: in 2017, CMS revised its SOW to read, “clinical validation is prohibited in all RAC (Recovery Audit Contractor) reviews.” CMS no longer specifies that a clinician must perform clinical validation; they say that they are no longer doing it at all. I’m not sure that all the RACs got that memo, either!

But I want to address Siraj’s last contention. When I became a physician advisor for a large multi-hospital system, the system chief medical officer (CMO) advised me to continue practicing clinically. As an obstetrician, he missed operating. I, on the other hand, believed that for the safety of my patients, there was a minimum threshold of hours to remain clinically competent, especially in terms of procedures. If a patient needed an emergency thoracotomy or tracheostomy, I was not the right person for that job. However, I was really good at my non-clinical physician advisor job, despite no longer practicing at the bedside. I am really good at deciphering documentation, and I have 25 years of clinical experience to back it up. I am more than capable of determining medical necessity and quality of care from the medical record, without seeing patients on a daily basis. I suspect that medical directors in insurance companies also have years of experience behind them.

That is not really the fundamental issue.

How people wield their knowledge and generate denials is the problem. Having artificial intelligence (AI) generate a zillion denials in a matter of seconds is a problem. Working on contingency, whereby throwing spaghetti on the wall is profitable, is highly questionable. Rejecting an appeal without weighing its merits is an issue. Having a bonus based on productivity and not on merit is a problem.

One of my superpowers is being able to see things from all sides. I believe the system as it is designed is important, with checks and balances. Providers shouldn’t be able to engage in fraud and abuse, and payors should have to pay for services legitimately rendered without throwing up roadblocks. The government is the biggest payor, and they get their money from me and you. We don’t want them to be squandering our taxpayer dollars, but we don’t want our hospitals to go bankrupt fighting ridiculous denials, either.

If providers deliver excellent medical care and document their thought process well, then payors should pay for medically necessary care of their beneficiaries. If any of these elements is not present, there should be consequences. Clinical validation is one cog in that process, and you don’t have to be an actively practicing practitioner to make that judgment.

Pediatric Sepsis Defined: Experts Endorse Organ Dysfunction

Pediatric experts have expressed their agreement: there is no such thing as sepsis without organ dysfunction.

By Erica E. Remer, MD, FACEP, CCDS, ACPA-C

Those of you who live in the adult world may not even be aware that the sepsis conundrum (i.e., Sepsis-2 vs. Sepsis-3) didn’t really pertain to pediatrics. That matter was tabled whilst the so-called grown-ups squabbled. Their previous criteria hailed from 2005, specifically from the International Pediatric Sepsis Consensus Conference. But it was already clear then that sepsis needed to be updated and better defined for the pediatric population as well, so an international consensus panel was convened in 2019, and the results were published online on Jan. 21, 2024.

The International Consensus Criteria for Pediatric Sepsis and Septic Shock (hereafter referred to as the International Consensus) were derived by 35 clinical experts from diverse pediatric practice in 12 different countries. The first thing that struck me was that they refer to a sentinel article titled Guidance for Modifying the Definition of Diseases: A Checklist, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) Internal Medicine in July 2017. It didn’t occur to me that there is a process to make adjustments in disease definitions. I wonder if it was crafted in response to the mess that arose after Sepsis-3 was introduced. The article explains that there is a fine line to walk between over-diagnosing conditions and capturing them early and often, versus harming patients by not entertaining a diagnosis quickly enough.

Something specific in that article struck a chord with me: “Diseases do not generally have discrete boundaries, and (my inserted word: clinical) judgment is required to determine the thresholds for diagnoses.” It seems as though it is more prudent to have many multidisciplinary representatives with expertise in the condition being addressed, making thoughtful decisions about diagnostic criteria than it being the Wild West, where everyone uses whatever criteria suit them that day – and for their own purposes.

The approach they took for the pediatric sepsis criteria was first to administer a global survey of 2,835 clinicians, published in The Current and Future State of Pediatric Sepsis Definitions: An International Survey, asking what the condition sepsis constituted and what the word should mean. I found this curious until I realized before there was even a Sepsis-1, we used to diagnose sepsis by gestalt. You walked in a room and said, “Uh-oh, this patient is really sick!”

The ultimate conclusion, supported by the majority of respondents, was that sepsis is an “infection with associated organ dysfunction.” The International Consensus authors noted that this was preferable to “infection-associated SIRS (Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome),” and that this evolved definition indicates “widespread adoption of the Sepsis-3 conceptual framework.”

Next, they undertook a systematic review of more than 3 million pediatric encounters, letting that inform the design of a derivation and validation study. The original concept was an eight-organ system model, but they ultimately dropped the renal, hepatic, endocrine, and immunological dysfunction criteria, seemingly to reduce “requirements for laboratory investigation and data collection.” I watched a presentation by the Children’s Hospital Association, and their commentary was that isolated hepatic, renal, endocrine, or immunological dysfunction was unusual, and it was far more common to be seen in conjunction with dysfunction of one of the other included systems, thus rendering those systems redundant.

The International Consensus settled on a composite four-organ system model, which was coined the Phoenix Sepsis Score (PSS). It seems as though the PSS was originally intended to be a prognosticating tool for mortality, similar to the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, but ultimately, attaining a score of 2 or more on the PSS was defined as identifying sepsis in an “unwell child with suspected infection.” Accruing ≥ 1 point from cardiovascular dysfunction establishes septic shock.

The PSS includes respiratory, cardiovascular (CV) (with age-based mean arterial pressure values), coagulation, and neurological systems. They are variably weighted, with CV potentially offering up to 6 points, respiratory up to 3 points, and the other two only up to 2 points. The score was designed to be able to be utilized even in low-resource areas.

There are a few more points regarding the International Consensus:

If a child manifests organ dysfunction remote from the site of localized infection, they are recognized as being at higher risk of mortality than if they only have a localized, single-organ system impairment (e.g., respiratory failure in pneumonia).

The PSS is assessed in the first 24 hours of presentation to the hospital. The article notes that the PSS “is not intended for early screening or recognition of possible sepsis and management before organ dysfunction is overt.”

Due to the difficulty of defining organ dysfunction in neonates born < 37 weeks’ gestation and the contribution of perinatally acquired infection, term newborns remaining in the hospital after delivery and neonates whose postconceptional age is younger than 37 weeks are excluded.

Here are some of my concerns regarding the International Consensus:

They use mortality as their only endpoint (morbidity is also a major concern post-sepsis);

They limited the development of the PSS to data from the first 24 hours of hospitalization (again, with the primary endpoint of predicting risk of mortality). Clearly, children with infections and organ dysfunction discovered later on, or who acquire infections during the encounter, can suffer from sepsis. I asked the corresponding author, and he asserted that they expect the PSS to perform similarly whenever during the hospitalization the condition crops up; and

If the Phoenix-8 score had comparable performance to the Phoenix-4 score (PSS), shouldn’t we diagnose sepsis if a patient has an infection and organ dysfunction not included in the PSS (e.g., hepatic or renal failure)? I’m going to hope that this is a rare occurrence, but what is the role for clinician judgment? Are payors going to deny claims of sepsis even if the clinician believes there is life-threatening organ dysfunction of a non-Phoenix-4 organ system?

This International Consensus statement certainly demonstrated rigor in development. The most important sentence to me in the paper is “SIRS should no longer be used to diagnose sepsis in children, and because any life-threatening condition is severe, the term severe sepsis is redundant.”

Fortunately, we have guidance permitting the capture of the code for severe sepsis if organ dysfunction is linked to the sepsis, even if the provider doesn’t document the word “severe.” Until the World Health Organization (WHO) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) eliminate the ICD-10/-CM code for severe sepsis without shock (R65.20), all patients with sepsis and sepsis-related organ dysfunction should receive at least four codes:

A code indicating sepsis (e.g., unspecified or organism-specific sepsis; perinatal, obstetrical, or postprocedural sepsis);

An R65.2- code indicating severe sepsis without or with septic shock;

A code specifying the underlying localized infection that is the source of the sepsis; and

At least one code detailing the organ dysfunction.

Pediatric experts have expressed their agreement: there is no such thing as sepsis without organ dysfunction.

Now, if we can only get the adult practitioners to buy in, too.

OIG Sets Sepsis in its Sights

Sepsis without organ dysfunction is…pneumonia or urinary tract infection or cellulitis. It doesn’t belong in the sepsis DRG, and I am going to predict that the OIG is going to agree with me.

By Erica Remer, DM, FACEP, CCDS, ACPA-C

I am going to begin a two-part look at sepsis, starting with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) focus on Medicare Inpatient Hospital Billing for Sepsis, brought to our attention by Dr. Ronald Hirsch; next time, I am going to write about updates to pediatric sepsis.

The introduction to the OIG’s plan to analyze Medicare claims for sepsis says some very impactful things. It asserts that “sepsis is the body’s extreme response to an infection,” and that “it is a life-threatening, emergency medical issue that often progresses quickly and responds best to early intervention.” It acknowledges that “the definition of and guidance for sepsis have changed over the years,” in an attempt to capture sepsis better. It identifies the issue that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) “currently recognize an older, broader definition,” and the OIG expresses a concern that hospitals may take advantage of the broader definition because they are financially incentivized to land patients in the relatively higher-weighted sepsis Medicare-Severity Diagnosis Related Groups (MS-DRG).

Their study will analyze patterns in inpatient hospital billing for 2023 and assess the variability of sepsis billing among hospitals. They plan to compare costs using the broader definition (i.e., Sepsis-2, according to SIRS, or systemic inflammatory response syndrome, criteria) versus the narrower definitions of sepsis, that is, Sepsis-3.

On Feb. 23, 2016, The Third International Consensus Definition for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), written by Mervyn Singer, Clifford Deutschman, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign followed up in March 2017, with their acceptance of the definition as “life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection.” Whereas Sepsis-3 defined the condition, Surviving Sepsis Campaign operationalized how to treat sepsis, issuing best-practice statements and utilizing the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) system. Prior to 2016, Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) was where we had derived Sepsis-2.

This was over seven years ago. Why are we still adjudicating this? If the sentinel organizations use the same definition, why don’t all hospitals everywhere use it? Why hasn’t SIRS been put to bed?

There are multiple reasons, and the reason the OIG is leveraging is the money. The relative weight (RW) for sepsis without mechanical ventilation > 96 hours with a major comorbid condition (MS-DRG 871) in 2024 is 1.9826, and its “without MCC” counterpart (MS-DRG 872) has a RW of 1.0299. For comparison, Respiratory Infections and Inflammations with MCC (MS-DRG 177) has a RW of 1.6964, with CC (MS-DRG 178) is 0.9867, and MS-DRG 179 without CC or MCC has a RW of 0.7633. The MS-DRG for urinary tract infections w/wo MCC (MS-DRGs 689 and 690) have RWs, respectively, of 1.1744 and 0.8069. Hence, the most profitable DRG for a patient who is admitted with an infection is in the sepsis set.

What other reasons enter into this persistent utilization of SIRS? Clinician ignorance or clinicians clinging to “the way it has always been done” are obvious factors. The fact that the core measures bundle and New York has its own criteria that don’t align with either Sepsis-2 or Sepsis-3 are others. There are also practitioners who, out of an abundance of caution, would rather err on the side of picking up “early sepsis” than missing the boat and having a patient die, so they would rather liberalize the criteria to catch cases that turn out not to be sepsis. I am supportive of making a tentative diagnosis early, but the key to compliance is to remove the diagnosis once it has been ruled out.

We all designed our sepsis alerts to use the general variable SIRS criteria because it was easy, convenient, and ubiquitous, but the diagnosis of sepsis always included other clinical indicators. For instance, altered mental status, hyperbilirubinemia, thrombocytopenia, and coagulopathy were included in the Surviving Sepsis Campaign 2012 table of diagnostic criteria for sepsis. But everyone gets vital signs taken and a white blood cell (WBC) count drawn if they have a potential infection, so those were attractive as a screening diagnostic tool.

SIRS is a great marker for clinically significant disease; however, it is very non-specific. Conditions not infectious in etiology may demonstrate tachycardia, tachypnea, fever, or elevated WBCs. Patients with infections may demonstrate those symptoms without having progressed to sepsis. It may represent an appropriate response to the infection.

I once was rounding with a provider who documented sepsis as her clinical impression on a patient who was on the fourth day of their admission and was sitting in bed smiling and eating a sandwich. I asked the provider if the patient met the criteria of sepsis – were they “sick” with a capital S? The provider replied that this wasn’t part of the definition. I disagreed, saying it was so integral to the definition of sepsis that the experts didn’t think they needed to explicitly say it. It is my opinion that the indication of being “sick” with a capital S is organ dysfunction.

I had a reader ask me once why I don’t want providers to diagnose “sepsis without organ dysfunction. Don’t you think that it is better to catch it early than to miss it?” My response was that patients who have infections should be treated aggressively and appropriately, whether or not they have sepsis. If you nip the infection in the bud and avert the development of sepsis, good for you!

Dr. Hirsch used a great analogy that I would like to reuse. He said lots of patients have chest pain without enzyme markers for heart attack. They will be monitored and might be catheterized and stented. We don’t make the diagnosis of impending myocardial infarction (MI) and get paid in an MI DRG.

When I review records in the context of clinical validation denials, invariably, most of the cases I find righteously denied are billed as sepsis. Sepsis without organ dysfunction is…pneumonia or urinary tract infection or cellulitis. It doesn’t belong in the sepsis DRG, and I am going to predict that the OIG is going to agree with me.

If your hospital still uses SIRS criteria, it’s time for them to transition to Sepsis-3. It’s time for the state of New York to transition to Sepsis-3. If your institution uses Sepsis-3, but your providers document poorly or inconsistently, they should be educated and monitored.

Clinical documentation integrity specialists (CDISs) should put a program in place to perform clinical validation of the diagnosis of sepsis. Clinical validation denials are predictable, and a pain, but nothing compared to an unfavorable OIG determination.

CMS IPPS Proposed Rule: Expansion of SDoH Designations as CCs

Consistent with the annual updates to account for changes in resource consumption, treatment patterns, and the clinical characteristics of patients, CMS is recognizing inadequate housing and housing instability as indicators of increased resource utilization in the acute inpatient hospital setting.

By Tiffany Ferguson, LMSW, CMAC, ACM

In its Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) Proposed Rule for the 2025 fiscal year (FY), the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is considering a change in the severity level designation for the social determinants of health (SDoH) diagnosis codes denoting inadequate housing and housing instability from non-complication or comorbidity (Non-CC) to complication or comorbidity (CC).

Consistent with the annual updates to account for changes in resource consumption, treatment patterns, and the clinical characteristics of patients, CMS is recognizing inadequate housing and housing instability as indicators of increased resource utilization in the acute inpatient hospital setting.

“Inadequate housing” is defined as an occupied housing unit that has moderate or severe physical problems, such as plumbing, heating, electricity, or upkeep issues. CMS describes concerns with patients living in inadequate housing by noting they may be exposed to health and safety risks that impact healthcare services, such as vermin, mold, water leaks, and inadequate heating or cooling systems.

Housing instability encompasses difficulties related to paying rent, overcrowding, frequent relocations, and/or other financial challenges associated with maintaining housing. While not directly citing from external sources, CMS asserts that studies have demonstrated moderate evidence linking housing instability to a higher prevalence of conditions such as overweightness/obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, as well as poorer management of hypertension and diabetes, with increased acute healthcare utilization among individuals with these conditions (CMS-1808-P). Expanding on this impact, CMS suggests that these circumstances could lead to limited or no access to prescription or over-the-counter medications, inadequate storage facilities for medications, and challenges in adhering to medication regimens.