Coding Info: Risk Adjustment and Congenital Conditions

Don’t continue to pick up Q codes just because they have risk adjustment implications.

By Erica Remer, MD, FACEP, CCDS, ACPA-C

A listener, who is a risk adjustment program manager, asked me to elucidate when a congenital condition code is appropriate. She was most interested in the cardiac conditions in the context of pediatric patients, but I thought it would be useful to go over all the aspects.

Congenital means a patient is born with an anomaly, or abnormality. It can be a physical deformity or a genetic or chromosomal abnormality. This is in contradistinction to an acquired condition which means the patient was born intact, but something happened, either accidentally or intentionally, and there is now an abnormal condition.

A good example is Q71.21, Congenital absence of both forearm and hand, right upper limb, versus Z89.211, Acquired absence of right upper limb below elbow. The latter could be from a farming accident, for instance, or by surgical amputation for a malignancy. Additional codes might provide those etiologic details.

According to the Coding and Reporting Guidelines, similar to codes from Chapter 16, Certain Conditions Originating in the Perinatal Period (the P codes), codes from Chapter 17, Congenital malformations, deformations, and chromosomal abnormalities (Q codes), are permitted to be used throughout the life of the patient.

In the current state of technology, a patient who has Trisomy 21 will always have Trisomy 21 coded. I say, “in the current state,” because there are new gene therapies that can effectively cure a genetic disease, like cystic fibrosis or sickle cell disease, and it is not out of the realm of possibility that other genetic or even chromosomal abnormalities may be conquered in the future.

Let’s address the conditions which interested Mary, congenital heart disorders. A musculoskeletal abnormality like the one noted above may be permanent and ongoing, so it is understandable that the code applies for the patient’s entire life. There are conditions which might be amenable to surgery, might require multiple surgeries, but even with those interventions, the condition may not be completely eliminated. For instance, hypoplastic heart syndrome (e.g., Q22.6, Hypoplastic right heart syndrome) may require multiple surgeries, and it may be alleviated, but the heart may never be rendered normal. That patient would continue to have Q22.6 for the duration of their life.

There are congenital heart defects which are diagnosed very early on, like ventricular septal defect (VSD) or patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), which may resolve spontaneously and completely without any treatment (I call that, “tincture of time”). Once the condition has resolved, the code to represent that will be found in Z87.7-, Personal history of (corrected) congenital malformations.

The parenthetical, “corrected,” is where the nuance of diagnosis and coding falls. If the VSD is large and doesn’t close on its own, surgery might be necessary to accomplish the closure. If it is successful, and the VSD no longer exists and is no longer clinically relevant, then it is “corrected.” Z87.74, Personal history of (corrected) congenital malformations of heart and circulatory system, would apply.

If, however, a congenital condition has been addressed but not “corrected,” it should still be coded as being present. Providers don’t understand the concept of “history of” as it is defined in coding. “History of” means old, resolved, no longer active, not being treated, and no longer impacting the patient, but may have the potential for recurrence or may influence the provision of future care. Maybe having that congenital issue and the surgery to correct it might portend problems in the future, like a higher likelihood of development of heart failure. That is why knowing the patient had a personal history of the condition and its repair is clinically significant, and a Z code is appropriate.

When should a coder pick up the condition? When the provider (hopefully accurately) documents that the condition is still present. If they document “history of” and it isn’t clear to the coder whether it is “chronic condition of” or “resolved historical condition of,” a query is indicated. I strongly recommend ensuring that the provider understands the “history of” concept before they respond to a query.

For risk adjustment purposes, any year when the condition still is present, the diagnosis should be documented and the code picked up. The year following successful and complete repair, the provider should document that the condition was “corrected,” and the Z code would then be applicable.

So, for instance, if a patient undergoes a successful reconstruction in February, for that entire year for risk adjustment purposes, the Q code would continue to be valid although after the recovery period is complete, the Z code demonstrating “history of” would then be appropriate for that given encounter. The following January, there would no longer be risk adjustment as only the Z code would be captured in that calendar year.

Don’t continue to pick up Q codes just because they have risk adjustment implications. You may get a financial boost at the time, but the compliance jeopardy is just not worth the risk.

Updates on Observation Services & Orders: United Health

This practice and strict policy run the risk of hospitals defaulting to a conservative stance to place observation orders when there is any uncertainty about the patient’s status, because of the anticipation of a potential UHC denial.

By Tiffany Ferguson, LMSW, CMAC, ACM

UnitedHealthcare (UHC) updated their hospital guidelines for observation services. This seemingly small update made Sept. 22, 2024, has led to notable behavioral changes regarding peer-to-peer conversations, claim denials, and rebills.

Previously, when hospitals received inpatient care denials, UHC permitted them to “rebill” the claim with observation services, according to their denial letters. However, it now appears that UHC is applying a similar approach to Humana, requiring an official order for observation services to be in place prior to patient discharge.

This shift indicates that the updated guidelines may reinforce the operational framework outlined in the December 2023 policy, which emphasizes the necessity of having an official physician order for observation services before discharging a patient. The policy clearly states that an observation status (UHC’s wording; this writer is well-aware that observation is not a status) must be established and documented with an order to avoid reimbursement denials.

A physician or qualified healthcare provider must place this order before discharge to ensure that services are appropriately billed. The absence of this order can lead to rejected claims and a lack of reimbursement for the hospital.

While the policy is explicit about the compliance requirements for observation, including not extending beyond 48 hours, it falls short in addressing situations in which a physician believes that a patient requires inpatient admission; UHC denies this authorization for their members.

According to UHC’s provider manual for coverage determination, the organization utilizes tools such as “UnitedHealthcare medical policies and third-party resources (like InterQual® criteria) to administer health benefits and determine coverage.” Notably, InterQual is owned by UHC, which raises questions about the independence of the criteria.

For patients whose inpatient status is denied by UHC, the hospital’s ability to adjust the claim hinges entirely on whether an observation order was placed before the patient left the facility – because the policy lacks clarity regarding the turnaround time for the reconsideration process if a denial is received. Typically, this occurs during the peer-to-peer process, which is scheduled “at a timeline provided by the UHC nurse on the call.”(2024, UHC Provider Manual).

Unfortunately, this could take place after a patient has already been discharged, making it impossible for the hospital to change the status determination prior to the patient’s departure if the peer-to-peer review upholds the denial. This practice and strict policy run the risk of hospitals defaulting to a conservative stance to place observation orders when there is any uncertainty about the patient’s status, because of the anticipation of a potential UHC denial.

However, without an observation order in place before the patient discharge, when clinically appropriate, hospitals face significant challenges in obtaining reimbursement. In such cases, the claim may be denied entirely, leaving the hospital to absorb the financial burden.

It is the continued practices of payers that are requiring hospital utilization review teams and physician advisors to up their games and work with providers to balance the clinical needs of patients with the behind-the-scenes requirements of insurers like UHC, ensuring that an observation order is placed, when necessary, and that it is well-documented and correctly coded.

The practice of utilization review is continuing to evolve, and requires a team of experts that are highly skilled and proactively efficient in regulatory guidelines and payor requirements to appropriately ensure the medical necessity and reimbursement for hospital services.

This is particularly true when payers such as UHC continue to evolve their policies and practices, making it harder for providers to achieve appropriate reimbursement for services.

Evaluating the Acute Hospital Care at Home (AHCAH) Initiative

CMS hosted virtual listening sessions to gather feedback from patients and caregivers involved in AHCAH. The responses were generally positive, with patients appreciating the convenience and personal nature of home-based care.

By Tiffany Ferguson, LMSW, CMAC, ACM

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has released a report on the Acute Hospital Care at Home (AHCAH) initiative, a program allowing select Medicare-certified hospitals to provide inpatient-level care within patients’ homes.

Originally launched to address hospital capacity challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, the initiative has continued under the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 (CAA), which extended the program’s flexibilities until Dec. 31, 2024. The recent report fulfills a mandate from the CAA to evaluate AHCAH and analyze its impact across multiple areas, including patient demographics, quality of care, and cost-effectiveness.

The study found that participating hospitals used a range of criteria to identify eligible AHCAH patients. These criteria, based on established hospital-at-home literature, ensure that selected patients are clinically appropriate for home care, and that their home environments are safe and conducive to receiving such care.

The report also highlighted demographic differences between AHCAH patients and traditional inpatients, showing that AHCAH patients were more likely to be white, live in urban areas, and have higher incomes, with fewer receiving Medicaid or low-income subsidies.

The report found that AHCAH primarily treated patients with a relatively small set of conditions, including respiratory and circulatory conditions, renal conditions, and infectious diseases. By grouping these conditions under MS-DRGs, CMS was able to compare treatment outcomes in AHCAH versus traditional inpatient settings. The findings provided insight into the types of cases that were most suitable for home-based acute care, suggesting that AHCAH may be particularly effective for certain known manageable conditions.

The CMS report also examined the quality of care provided under the AHCAH initiative. It assessed metrics like 30-day mortality rates, 30-day readmission rates, and the occurrence of hospital-acquired conditions (HACs). The findings indicate that AHCAH patients generally had lower mortality rates than their hospital-based counterparts.

Readmission rates, however, varied by condition, with AHCAH patients showing significantly higher rates for some conditions and lower rates for others; however, these specific conditions were not mentioned in the publicly released fact sheet. HAC rates were lower for AHCAH patients, although differences were not statistically significant.

When evaluating cost and utilization, the report focused on factors like length of stay, Medicare spending after discharge, and hospital service use, including telehealth services. AHCAH patients typically had longer lengths of stay, but incurred lower Medicare spending, in the 30 days following discharge. While these findings suggest cost benefits, the complex nature of AHCAH’s patient selection and clinical conditions makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions about overall savings compared to inpatient hospital settings, according to CMS.

CMS hosted virtual listening sessions to gather feedback from patients and caregivers involved in AHCAH. The responses were generally positive, with patients appreciating the convenience and personal nature of home-based care. Clinicians, too, reported favorable experiences, which aligned with broader hospital-at-home research indicating high satisfaction rates among patients receiving care at home.

The report concluded with a need for further research and development, including refining cost, quality, and utilization metrics.

With the AHCAH initiative set to expire at the end of 2024, its continuation depends on future congressional action.

Having a Patient Advocate is Critical to Optimize Patient Care

It would be optimal for everyone to have an advocate as they try to navigate the morass which is our healthcare system.

By Erica Remer, MD, FACEP, CCDS, ACPA-C

I have been dealing with family issues since the end of September. My father-in-law (FIL) fell ill, and I have had to help out. Many of you also know my father is in a memory care unit, and I visit him daily and manage his affairs. I constantly wonder what people do if they don’t have a me. Today I am going to talk about how to be a healthcare advocate for another individual (I will refer to this as “your person.”).

The first thing you should do is get a notebook to keep ongoing records. Taking meticulous notes is critical. I suggest you start right now, before an acute incident occurs or as soon as you are recruited to be a medical advocate. Having an accurate medical history (past medical history, history of present illness) is very helpful for the healthcare provider (HCP). If something happens which leads to a medical encounter, document the sequence of events as you understand them. You will need to repeat them over and over again.

Your person needs to give HIPAA permission for you to be privy to their protected health information. If they are conscious and competent, they can do it verbally. The HCP should ask something like, “Is it ok if we discuss your condition in front of your daughter?” If the patient agrees, that is considered consent.

You might consider having a formal HIPAA release form signed so the healthcare providers know you are entitled to be engaged in healthcare discussions. A sample is found here: https://www.hipaajournal.com/hipaa-release-form/. My interpretation is that Section I should have “anyone”, and Section IV should have your name and information. Again, do this proactively – once your person is unconscious, it is too late. Have a printed physical copy and a digital copy in a cloud somewhere.

Arrange to have electronic access to their portal if you can. It is great to be able to access a medication list, notes from prior visits, names of physicians, etc. on the fly.

Being an advocate, you will be exposed to information about your person that they might want kept confidential. You should consider it your duty to keep anything you hear or witness private unless your person allows you to share it (e.g., you are the family contact person).

What if your person makes plans set out in a living will? That’s great; they are expressing their wishes, but living wills are legal documents specifying decisions if a person becomes terminally ill or permanently unconscious. It is also useful to have a durable power of attorney for health care (DPOAHC). This document names surrogates who are given permission to make all medical decisions for the individual in the case that they deemed not competent to make their own decisions, but the patient doesn’t necessarily need to be terminally ill or in a vegetative state. The healthcare proxy is supposed to make decisions according to their understanding of what the patient would want. The living will often helps guide their decisions. These documents should be crafted long before they are needed. If you wait too long, it may be too late. If you are the DPOAHC, you have the legal authority to make medical decisions for the patient if the patient is not capable of making their own decisions, as opposed to just sitting in and giving advice as an advocate.

As an advocate, you may consider requesting permission to record discussions with doctors. 50-80% of medical information provided by HCPs is forgotten immediately after the interaction. Explain you have a concern that you will not understand all of the jargon or not be able to remember the details. Many states permit you to record even without the other party’s consent, but not all; in any case, providers would appreciate the heads up. Cell phones are ubiquitous; if legally permissible, you can use ‘voice memos’ or some other function that can record audio.

When you take notes in your notebook, try to make them as legible as possible. My sister-in-law and I were tag-team advocating for my FIL, so the notebook was communal as we switched off. If there are details that you want to be able to recall from home without access to the notebook, take a picture on your phone or take notes from the notes.

What should be in the notes? Write down the date and time of the interaction, the HCP’s name and specialty, and what they say. They often use doctor-speak and if you are not clinical, it can be confounding. DO NOT HESITATE TO ASK FOR CLARIFICATION! Do not feel stupid or silly or like you are bothering them. The point is for you and the patient to understand what is going on and to be able to make informed decisions about their care. Read back what you understood the provider to have said and what you documented, to ensure accuracy. If you can’t spell something, ask the clinician to spell it for you. Most likely, you will want to confer with Dr. Google later.

You should try to take yourself out of the equation and ensure that it is all about the patient. Start sentences off with “The patient needs to know…” to keep it patient-centric.

Don’t reserve note-taking for the doctors or nurse practitioners. Take notes when you speak to the case managers or the physical therapist or the nurses. If your person is left in bed calling for a nurse for 35 minutes, that is important information. Is it a once-off or a pattern of neglect? Is it a single individual or the entire staff? If there is an adverse interaction, try to take direct quotes as opposed to paraphrasing.

Don’t divide your attention. When the HCP is in the room, don’t look at your phone to review texts or scroll through social media. Don’t be chatting with someone else. You will have a limited amount of time with any given practitioner; don’t squander it.

Speaking of which, many providers have a routine as to when they round. If you can, find out what it is and try to be present when they do. If you can’t be there then or their rounding is unpredictable and you missed their visit, ask the nurse to page them and request them come at their convenience to talk to you and the patient again.

I think one of the most important roles an advocate has is to educate the HCP as to the patient’s baseline. As an emergency physician, I saw patients at their most vulnerable and worst times. It was crucial for someone to let me know that this patient with metabolic encephalopathy from overwhelming sepsis was driving and calculating his taxes two days before presentation. It helps inform expectations for recovery.

If you have a question, ASK IT! You don’t want to have that little detail be the reason something untoward happens when it is not addressed, like you noticed your person’s speech was garbled for 5 minutes after they got back to the bed from the bathroom but no one else witnessed it, or “Why hasn’t he gone to the bathroom for the last 10 hours while I’ve been here? I’ve had to go twice.” (The answer was he had urinary retention and there was 1400 cc of urine in his massively distended bladder) “Why is my father’s pacemaker pocket red?” led to the discovery of a pacemaker infection. If I had assumed they had noticed it and not asked…

Be tuned in to your person. If they get a quizzical look on their face, ask the provider to repeat whatever just confused them. If they are hard of hearing and you are familiar with the behavior of them saying they heard you when they didn’t, ask the provider to speak louder and more slowly (I also taught a nurse the trick of the poor-man’s hearing aids. You flip a stethoscope around, put the earpieces into the patient’s ears, and speak into the diaphragm). If there is a language barrier, it is not your responsibility to translate. The patient has a right to translation services. Exercise that. It is your job to advocate for your person, not to translate for the staff.

There are certain basic issues which need to be addressed. Make sure you bring the hearing aid charger and remind the nursing staff to charge hearing aids overnight. It is exasperating for your person to not be able to hear because their hearing aids are dead. It is a reasonable expectation that dentures will be removed and cleansed overnight. Bring a long charging cord for your person’s phone so they can have it charging and can reach it whether they are in the bed or the chair. Bring wipes to clean glasses, a glasses case for night-time, and encourage the nursing staff to make sure their glasses are on their face in the morning. Make sure everything is labeled. If you don’t have access to a label maker or Sharpie, you could ask the nurse for a hospital sticker and use that.

My FIL was becoming psychotic because his day-night cycles were all confused. His room had a window into a central enclosed atrium so there were no light cues as to time of day. There was a remote-controlled electronic window shade for privacy which made it look like nighttime, which was often left in the down position. I purchased him a digital clock “for dementia patients” (although he doesn’t have dementia) which has a visual cue as to time of day (morning, afternoon, night).

One of the most important things an advocate can do is ensure that basic hygiene needs are attended to. Patients need to brush their teeth and shave. The advocate doesn’t need to perform these tasks, but they can ensure that the nursing staff does. Make sure the electric razor is charged, and the charger and razor are labeled. I kept chargers (e.g., razor, phone) corralled in a canvas bag.

As an aside, take care of yourself, too. Bring a water bottle, your cell phone charger, and snacks. Bring a sweater or jacket because it may be chilly or hot in the patient’s room. Bring a book or work because there is likely to be down-time while your person dozes.

It is critical that the patient mobilizes as soon as it is safe, and they are able. The difference between being discharged to home or going to a rehab facility can be getting up and moving around. It is easier for aides to use devices to get the patient to the bathroom or only having them transfer 3 steps to a chair. It takes more time to walk the patient to the bathroom or out into the hallway, and all facilities are understaffed. You might think that physical therapy will effectuate this, but often their role is to assess the patient’s function for discharge planning purposes. They may only see the patient once or twice in a stay. If you are capable and it is safe to do so, get your person up and around as soon as possible.

Most of the points I am making were my observations and thoughts from my own experience. However, I did some research and was reminded that it is a great practice to ask anyone preparing to touch your person to wash their hands (Tips for the Advocate When Talking to the Doctor (or another clinician). Regarding their checklist, I personally wouldn’t ask my person if I should ask the question; I would phrase it as, “Is it ok with you if I ask clinicians to wash their hands before they touch you, because there are many unnecessary deaths from hospital-acquired infections every year?”

If you have a healthcare provider in your life, e.g., your brother is a paramedic, your aunt is a doctor, your friend is a nurse, now is the time to ask them to help you make sense of what is going on. They may be able to give you insight or advice. They may lead you to a website or society which can be helpful. I also recommend making sure that your person’s primary care physician or other caregiver is aware of the situation. They may have information useful to the current HCP.

The last thing I would like to address is examples of questions you might be thinking about and asking:

Do we know why this is happening now?

The last time this happened, they had to do [X procedure] or they gave her [X medication]. Do they need it again?

Could this be medication related? Could this be related to the new medication that was started last week?

What did the tests show? What do those results mean? Can the patient have a copy of those reports/tests?

Do we need a [specialty] consultant to see him here in the hospital?

You said you were going to start him on [medication X] yesterday? Did he get his first dose of it? How long before we should see effects?

Could we try removing the Foley catheter and see if he can void spontaneously prior to transfer to rehab?

What exactly is the diagnosis? What is the prognosis?

When do you think she will be discharged? I know PT recommended a skilled nursing facility, but could it be accomplished safely at home with home health care?

It would be optimal for everyone to have an advocate as they try to navigate the morass which is our healthcare system. I hope this article will give you some tips on how to be an advocate for your person. I wish you all the best of luck.

References:

Step 5: Use and Advocate, Be an Advocate for Others

Joint Commission: Use and Advocate or Be an Advocate for Others

Discharge Summaries Make a Difference

My philosophy is that a correct and complete set of discharge diagnoses can be used to reconstruct the entire patient encounter.

By Erica Remer, MD, FACEP, CCDS, ACPA-C

My husband was speaking in Maui at the beginning of March 2020, and I came down with COVID-19 on the airplane. After a serendipitous dinner with his brother, who lives in Dallas, I was quite ill, and my infection limited our activities. The weather was delightfully tropical. On our last day in Maui, we went whale watching, which was spectacular. We saw a collection of approximately 15 whales, which swam under our boat. Erick got miserably seasick, which threatened our flight to Oahu. There, we had a somber visit to Pearl Harbor, punctuated with about 10 glorious rainbows. Our penultimate day, we did an island tour.

You just read a summary of my vacation. I condensed the entire encounter of 10 days into eight sentences. Did you get enough information about the trip?

It depends what you are going to use the information for. If you are just being caught up on my travels, sure. Are you going to try to replicate our itinerary and activities? Then, no. If I had journaled our adventures, there would have been more specifics I could have shared with you, if you were so inclined to read them. Where we went, how much it cost, what we saw. However, if your trip was scheduled two weeks after mine, but you didn’t receive my trip summary until a month later, it wouldn’t be at all helpful.

Why do providers generate a discharge summary? The short answer: because they have to. It might be even more important to determine what the provider perceives a discharge summary is for. If they think it is busy work, and just fulfilling the directive of some administrative body, then the quality might suffer. If they believe it is valuable communication of the patient encounter for the follow-up physician and anyone else who might be reading it, then it is more likely to be detailed and illuminating.

Discharge summaries have elements mandated by the Joint Commission:

Reason for hospitalization (patient presented complaining of fevers, rigors, and cough);

Significant findings (physical exam demonstrated hypoxemia and confusion. CXR demonstrated a large RML pneumonia and blood cultures grew out Streptococcal pneumoniae. Diagnosis: Sepsis due to S. pneumoniae pneumonia with hypoxemia and metabolic encephalopathy);

Procedures and treatment provided (supplemental oxygen, intravenous fluids, and ceftriaxone administered. Sepsis protocol followed and infectious disease consult obtained. Sepsis resolved on Day 2.);

Discharge condition (discharged in improved and good condition);

Patient and family instructions (finish course of antibiotics, follow up with PCP next week, and return to ED for shortness of breath or concerning symptoms); and

Attending physician’s signature.

It strikes me that the mandated elements are sparse. If I had determined the required elements, I would have explicitly included the hospital course, outstanding issues of which the follow-up professional needs to be aware, and a list of final discharge diagnoses.

The Transitions of Care Consensus Conference (TOCCC) attempted to develop standards for transitions of care from the inpatient to outpatient setting. They also recommended the following elements, which would be included in the “ideal transition record,” and isn’t that what a discharge summary should be?

Patient’s cognitive status;

Emergency plan, person and contact number;

Treatment and diagnostic plan, including a current, reconciled medication list;

Prognosis and goals of care;

Advance directives, power of attorney, consent;

Planned interventions, durable medical equipment, wound care, etc.;

Assessment of caregiver status; and

Inclusion of the patient and caregivers in the development of the transition record to take into consideration the patient’s health literacy, insurance status, and cultural sensitivity.

Some of these seem more appropriate for the transition to another institution (e.g., skilled nursing or assisted living facility) than to home, but the essence is: provide the information that will be useful for the receiving clinician and/or institution.

The literature focuses on the need for aftercare providers to receive information, and on medicolegal considerations. It fails to mention that coders and billers also rely on accurate, complete, and timely discharge summaries. On the inpatient technical side, diagnoses are eligible for coding if they are present at the time of discharge or demise, and the discharge summary represents the prime and final opportunity to record diagnoses destined to be coded. My philosophy is that a correct and complete set of discharge diagnoses can be used to reconstruct the entire patient encounter. This ensures that the patient lands in the appropriate Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) and the correct tier, for reimbursement.

Many institutions have templates for necessary components of a discharge summary. To design the ideal document, involve the appropriate parties. This should, at very least, include the people who will be generating the document and a representative of the folks who will be relying on the document, post-discharge. Compliance should ensure that the mandated elements are included. Information technology needs to be present to determine how to operationalize the endeavor.

If it were possible to start generating upon admission a discharge summary that could be finalized, dated, and inserted in the appropriate location in the medical record upon discharge, I would support that. It could be leisurely composed in a stepwise and thoughtful fashion.

At admission, the chief complaint and a brief history of present illness could be introduced. As the patient encounter progressed, the hospital course could be recorded in real-time. Each day, a sentence or two could be added, with revisions of the previous days’ entries for accuracy and clarity.

(e.g.,

Day 1: Awaiting ID consult.

Day 2: ID consult considering necrotizing fasciitis. Ordered CT scan.

Day 3: ID consult ruled out necrotizing fasciitis when CT scan did not reveal gas in soft tissue.).

A running summary could serve dual purposes; in addition to ultimately being inserted as the synopsis for the discharge summary, it could also inform caregivers during the encounter. If a patient crumps, the provider doesn’t have the time or inclination to read the entire chart – they just want the down and dirty, which will help them care for the patient right now. A concise running summary would be just the ticket.

When I was a physician advisor, we implemented an electronic summary. It drew in elements from multiple already established electronic sources to try to minimize duplicative effort. It pulled in the current medications from the MAR (medication administration record), and the provider could notate which ones were indicated for homegoing. It imported recommendations for physical and occupational therapy.

If labs or other tests were pending or scheduled, it recorded them. It was (and probably still is) very useful and timesaving. My contribution was to create a radio button that the provider had to click, which indicated whether the patient had expired. If so, it prevented the discharge (now, death) summary from including homegoing medication and instructions and follow-up appointments, now unnecessary and misleading.

Having the ability to construct a discharge summary rapidly from different sources can result in disjointed information if no one ensures that it is edited, revised, and accurate. It can, however, also result in a discharge summary being promptly available for review. Maybe it will be an opportunity for artificial intelligence (AI), to ensure that the narrative reads fluently.

Consider surveying your end-users (e.g., PCPs, nursing home providers) as to whether the data delivered to them was complete, succinct, timely, and usable. You could share their responses with your practitioners, and that might encourage the clinicians to craft excellent and useful discharge summaries.

A final tool in your armamentarium could be targeted feedback. Design an audit tool for discharge summaries and task those individuals who read the summaries to use the tool to assess the quality of the documents. There should be a section on the audit tool for comments and suggestions. Compile statistics and share the information and examples with the summaries’ authors.

Remind the providers that someone is reading these documents, they care what the discharge summary says, and it makes a difference in the patient’s longitudinal care.

Building the Bridge Between UR and CDI

Technology firms such as Iodine are making significant strides in bridging UR and CDI, enhancing transparency and efficiency in collaborative learning.

By Tiffany Ferguson, LMSW, CMAC, ACM

Dr. Erica Remer and I had the pleasure of co-presenting at the Healthcare Financial Management Association (HFMA) Region 6 Conference in September in Columbus, Ohio. Our topic was the intersection of utilization review (UR) and clinical documentation improvement (CDI), examining the current state of these disciplines and offering predictions about their future directions.

Our presentation aimed to provide clinical relevance to a healthcare financial and revenue cycle audience.

In previous articles, I have explored why these two disciplines have historically been separate. Key reasons include differences in technology and the distinct roles UR and CDI play; UR traditionally aligns with case management, and CDI with coding. However, the landscape is evolving. Technology firms such as Iodine are making significant strides in bridging UR and CDI, enhancing transparency and efficiency in collaborative learning.

Other technology platforms are also recognizing the importance of uniting these two areas to form a cohesive clinical revenue cycle.

While the partnership between case management and utilization review remains essential, the increasing focus on the social determinants of health (SDoH) and transitional care across the care continuum is continuing to shift case management’s role. It is becoming more integrated with population health, creating new opportunities for collaboration with outpatient services.

To foster greater collaboration between UR and CDI, and to improve efficiency, I recommend the following steps for consideration today:

Incorporate Collective Learning: Include both UR and CDI teams in shared educational sessions. For example, webinars aimed at CDI should also include UR staff, and vice versa.

Build Unified Dashboards: Develop dashboards that provide a comprehensive view of both UR and CDI activities. For example, patient status conversions affect CDI review times, and short-stay conversions to inpatient status influence CDI’s capture rate of chronic conditions (and ultimately impact case mix index) – putting both groups at risk for denials, either for medical necessity or DRG downgrades.

Expand Outpatient CDI: Consider having your CDI specialists review observation cases to identify opportunities for capturing Hierarchical Condition Categories (HCCs) or even help with queries to support improved documentation, which may create greater defensibility for inpatient conversion.

Align Physician Communication: Ensure that documentation improvement efforts convey unified messages from both UR and CDI. This can reduce confusion and reinforce the importance of thorough documentation for multiple areas, including quality, level of care, denial management, and coding.

Integrate CDI into UR Reviews: Explore how the UR team can incorporate CDI initial reviews into their concurrent review process for payers. Greater transparency to see what the CDI specialists are querying may help the UR team see potential risks in the continued stay.

The convergence of UR and CDI is essential as we move toward a more integrated healthcare model. Technology is playing a pivotal role in bringing these traditionally separate disciplines together, allowing for better communication, efficiency, and financial outcomes. By fostering collaboration through shared learning, data transparency, and unified communication efforts, healthcare organizations can enhance their clinical revenue cycle while delivering high-quality patient care.

The future of UR and CDI lies in breaking down silos and working cohesively to adapt to the rapidly changing demands of healthcare.

New from CMS: “Age-Friendly Hospital Rating”

The Age-Friendly Hospital measure aims to ensure transparency and consistency in hospital reporting, allowing CMS to monitor and improve the quality of care delivered to older adults across the healthcare system.

By Tiffany Ferguson, LMSW, CMAC, ACM

The Age-Friendly Hospital Rating is a new structural measure included in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) 2025 Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) Final Rule.

This measure is designed to assess hospitals’ commitment to delivering high-quality care to patients 65 and older. The rating focuses on five key domains: patient goals, medication management, frailty screening, social vulnerability, and leadership commitment.

Hospitals must affirmatively attest to these domains to demonstrate their compliance with best practices for older adults. The implementation of this measure includes specific data collection and submission requirements, as outlined by CMS.

Under the 2025 IPPS Final Rule, hospitals and health systems are required to submit data for the Age-Friendly Hospital Rating measure on an annual basis. The data submission is structured around the five domains, and hospitals must evaluate whether they meet the criteria for each domain fully to receive credit.

Partial compliance with a domain does not earn points, meaning hospitals must engage with all the elements within a domain to receive one point for that area. For example, in the domain focused on frailty screening and intervention, a hospital must meet all corresponding attestation statements to earn a point. This includes a requirement to screen for risks of malnutrition, mobility, and mentation, upon admission or before major surgery. Qualifying plans must submit management plans, and data collection is required.

This measure also requires processes to lower the risk of delirium in the emergency room.

The data collection process is streamlined through the CMS Hospital Quality Reporting (HQR) system. Hospitals will use this tool to submit their data once per year. The CMS tool will collect the hospitals’ attestation statements for each of the five domains, verifying whether they can affirmatively attest to engaging in the best practices defined by CMS for the care of older adults.

Additionally, the IPPS Final Rule mandates that hospitals report their measure results, regardless of their responses to the attestation questions. This reporting is part of the pay-for-reporting structure of the Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) Program, which ensures that hospitals provide transparent data about their care practices for older adults.

Hospitals are not penalized financially for their attestation responses, but are required to submit accurate and timely data through the HQR system.

Hospitals must submit this information annually, with mandatory reporting beginning in the 2025 reporting period. The Age-Friendly Hospital measure aims to ensure transparency and consistency in hospital reporting, allowing CMS to monitor and improve the quality of care delivered to older adults across the healthcare system.

Although many of the measures in this initiative overlap with other quality reporting requirements, it may be beneficial to review and ensure there is a crosswalk with the initial nursing documentation, therapy evaluations (PT, OT, and ST), and case management/social work documentation to ensure that information is easy to extract for data collection, reporting, and future interventions.

CMS OPPS Proposed Rule: Considerations for Outpatient Social Drivers

It will be a massive undertaking to determine how these questions will be provided to patients and how appropriate follow-up will be conducted when a patient responds positively to one of these questions.

By Tiffany Ferguson, LMSW, CMAC, ACM

If you’ll recall, I recently reported on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Proposed Rule for the social determinants of health (SDoH) in the outpatient settings, specifically Hospital Outpatient Departments (HOPDs), Rural Emergency Hospitals (REHs), and Ambulatory Surgical Centers (ASCs).

To recap, CMS has proposed in the 2025 Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) Rule an expansion of the SDoH initiatives for quality reporting, with a similar staged rollout to what we experienced during the Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) rule for the 2024 mandate. The same measures and processes used in hospitals for inpatients 18 and older are proposed to be incorporated into the Hospital Outpatient Quality Reporting (OQR), Rural Emergency Hospital Quality Reporting (REHQR), and Ambulatory Surgical Center Quality Reporting (ASCQR) programs.

Voluntary reporting will begin with the 2025 reporting period, followed by mandatory reporting in the 2026 reporting period/2028 payment or program determination.

Logistical Considerations for Implementation

Similar to the inpatient setting, the SDoH measure in outpatient settings will be calculated based on each outpatient encounter for patients 18 and older. Patients must be offered five specific Health-Related Social Needs (HRSN) domain questions related to personal safety, utilities, housing, transportation, and food insecurity during their care in a HOPD, REH, or ASC (https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/07/22/2024-15087/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-hospital-outpatient-prospective-payment-and-ambulatory-surgical). The first measure will evaluate the proportion of patients who are offered the screening tool versus those who actually complete the questions. There are exclusions for those unable to complete or refusing to undergo the screening, which must be appropriately documented. CMS highly recommends that the tool be electronic.

Additionally, the Screen Positive Rate for SDoH measure will report on the percentage of patients who screen positive for one or more HRSNs. This data will be reported separately for each of the five HRSNs, allowing healthcare providers and policymakers to understand the prevalence of specific social risks in different care settings. The data will be reported annually. This will also provide continued data support for Z code capture.

Challenges in Operationalizing SDoH Screening

While this screening tool marks a critical step toward addressing the SDoH on a broader scale, there are legitimate concerns regarding how to operationalize this process when a patient screens positive – and determining who will follow up on those needs. Currently, HOPD encounters include lab, imaging, radiology, bedded outpatients, same-day surgery, physician offices, and infusion departments, to name a few. It will be a massive undertaking to determine how these questions will be provided to patients and how appropriate follow-up will be conducted when a patient responds positively to one of these questions.

To prepare for this rollout, HOPDs, REHs, and ASCs should start discussing the following:

Mechanisms for incorporating SDoH Screening into the Registration Process: Consider integrating these questions into your patient portal, to be completed before or at the time of check-in. This will streamline data collection and quality reporting. HOPDs, REHs, and ASCs will need to assess all portals of entry to ensure that these questions are being provided for applicable patient encounters. It will be valuable to consider prior patient responses from previous encounters with an update-and-validate approach, rather than starting from scratch each time.

Plan for Escalation and Triage: Develop a process for how organizations will respond to positive SDoH screenings. Something hospitals, and particularly case management departments, have learned from responding to the numerous positive screens on the inpatient side is that not all questions require immediate follow-up, nor is the patient always interested in assistance.

Consider including a question that asks if the patient is already receiving assistance for each need. The questionnaire should also include a question as to whether the patient would like to speak to someone further about their response. If the answer is no, follow-up may not be required, and should be documented as such. If the answer is yes, determine if the issue can be addressed via a phone call at a later date or if someone should be available to address the need during the visit.

Immediate action should be taken for concerns related to personal safety, while issues related to housing, utilities, food, and transportation could be routed to appropriate teams for timely but non-immediate follow-up. This approach could involve partnerships with community organizations, ambulatory care management departments, post-acute resource centers, or telehealth/phone-call outreach services, likely some type of case management outreach support.

Although we do have time to prepare, as we have seen from the inpatient SDoH initiative, using the voluntary reporting period if this ruling is finalized will be a key method for trialing various strategies to ensure appropriate outreach and follow-up occurs. As you can expect, I will continue to follow this ruling and see where CMS lands in their finalized determination.

Important Information Concerning Aetna

This policy is designed to reduce unnecessary readmissions, which Aetna views as a risk to patient safety and a burden on healthcare resources.

By Tiffany Ferguson, LMSW, CMAC, ACM

Aetna’s recent policy update, which became effective July 1, marks a significant change in how the insurer will manage hospital readmissions.

Previously, Aetna’s Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) Readmission Policy focused on individual facilities by using the Provider Identification Number (PIN). The new policy now applies at the Tax Identification Number (TIN) level, meaning entire health systems are being evaluated as a single entity.

Although this does appear to have been a previously held practice by Aetna in some of their Medicaid products, such as Aetna Better Health, this new update will globally apply to all of Aetna’s products, unless there are state or provider contracting provisions to limit such practices.

This change was briefly mentioned in Aetna’s April 2024 update: “We want to improve the quality of care and general health of our members. Readmissions can put our members at risk for unnecessary complications. We currently apply the Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) Readmission Policy on hospitals at the Provider Identification Number (PIN). Effective July 1, 2024, we will apply the policy at the Tax Identification Number (TIN).”

This broader scope means that if a patient is readmitted to any facility within the same health system, the readmission could be flagged and potentially denied, even if the initial and subsequent admissions occur at different locations. This policy is designed to reduce unnecessary readmissions, which Aetna views as a risk to patient safety and a burden on healthcare resources.

This statement is interesting, as reports were recently released regarding the fact that Aetna’s operating income is down 39 percent, or $938 million, from the prior year. Conveniently, Aetna’s stricter criteria will result in higher denial rates, impacting reimbursement and patient care.

Health systems must now closely examine their discharge processes, post-discharge follow-ups, and care coordination across all facilities under the same TIN to avoid preventable readmissions. However, in reviewing Aetna’s policy, it becomes clear that health systems are able to request reconsideration to contest any denials that are potentially unrelated or were the result of a scheduled procedure.

Aetna’s expansion of its DRG Readmission Policy to the TIN level is a strategic move to improve patient outcomes by reducing avoidable readmissions – and to likely yield financial benefit to Aetna. Health systems should proactively adapt their procedures to minimize the financial and operational impacts of this policy change.

Recommendations should be considered to check internal contracting language and state protections and to continue to adopt care transition protocols that will help with readmission prevention.

A New Code: Z51.A, Encounter for Sepsis Aftercare

Dying is not the only consequence of sepsis. Besides the fact that sepsis survivors are at higher risk for another bout of sepsis from a subsequent infection (and for readmission), there are potential sequelae of sepsis, especially if a patient was in an intensive care unit.

By Erica Remer, MD, FACEP, CCDS, ACPA-C

Today I am going to focus on a new ICD-10-CM code, as of Oct. 1: Z51.A, Encounter for sepsis aftercare.

We think about sepsis mortality a lot. Since there isn’t a universally applied definition of sepsis, exact rates are elusive. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 75 percent of sepsis deaths in the United States are in the Medicare population, and the death rate for this group exceeds 300 deaths per 100,000 people.

The death rate is higher for men, as opposed to women, Blacks compared to others, and rural versus urban dwellers, and mortality also is noted to increase with age.

Dying is not the only consequence of sepsis. Besides the fact that sepsis survivors are at higher risk for another bout of sepsis from a subsequent infection (and for readmission), there are potential sequelae of sepsis, especially if a patient was in an intensive care unit. The condition “post-sepsis syndrome” (PSS), which includes long-term physical, cognitive, and psychological effects after surviving sepsis, affects up to half of all sepsis survivors.

A nice graphic detailing the manifestations of PSS can be found in this article: Understanding Post-Sepsis Syndrome: How Can Clinicians Help? Physical manifestations of PSS can include dyspnea, heart failure, chronic kidney disease, immunosuppression, fatigue, and muscle and joint pain. Mental effects include post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, deranged sleep, and memory deficits.

There are striking similarities and overlaps between PSS, post-intensive care syndrome (PICS) and post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (PASC). Most patients who develop PSS and PICS had been gravely ill; long COVID can persist even after a seemingly minor bout of COVID-19. That condition is the only disorder that has a dedicated ICD-10-CM code, U09.9, Post-COVID-19 condition, unspecified, and the specific condition (e.g., loss of smell or pulmonary embolism) is meant to be coded first.

There is no way to code PSS in ICD-10-CM at the present time.

Once resolved, there is no way to capture that a patient had suffered and survived sepsis. After resolution, a code indicating sepsis (e.g., A41.9, Sepsis, unspecified organism) is no longer appropriate, because that is for an acute and current episode of sepsis. Z09, Encounter for follow-up examination after completed treatment for conditions other than malignant neoplasm, is non-specific, requires an additional code to identify any applicable history of disease code, and would not be considered appropriate if there were persistent issues related to the condition, because treatment would not be “completed.” Z86.19, Personal history of other infectious and parasitic disease, is again non-specific and is not appropriate if there are ongoing medical issues.

As a result, University of Colorado/UCHealth submitted a request to the CDC for a code to indicate sepsis survivorship (Topic Packet March 2023), and it was discussed in the Coordination and Maintenance Committee Meeting in March 2023. In particular, UCHealth felt that post-acute care and home health care could benefit from having a means to signify continued recovery from sepsis. They felt that increased awareness among healthcare providers and policymakers would be beneficial, and that it would be easier to perform epidemiological monitoring post-sepsis.

Z51 is Encounters for other aftercare and medical care, and we are instructed to also code the condition requiring care. Since the condition is still ongoing, there is an Excludes1 for using the follow-up exam after treatment code, Z09. I would envision that a primary care provider following up after a hospitalization for sepsis, home health continuing care, physical or occupational therapy, and post-acute facilities will welcome the ability to assign Z51.A, Encounter for sepsis aftercare, to explain why they are treating ongoing sequela. It is not entirely clear to me for how long this code would be utilized. If there are ongoing manifestations, obviously. But the increased of risk of recurrent sepsis is for at least a year, even if there are no long-lasting obvious sequelae.

I wish they had developed a specific code for personal history of sepsis, too. I think there will be times when there is no longer sepsis aftercare being provided, but it would be useful to know that a patient had the condition in the past and might be vulnerable to another episode now. Z86.19 is too vague for me.

There’s a big difference between having had the chicken pox or strep throat and sepsis.

Until this is all sorted out, I am still grateful for this new code. I think it will contribute to our overall understanding of sepsis.

Proposed Ruling Focuses on Social Drivers in Outpatient Settings

The expansion of SDoH screening to the outpatient setting aims to align and enhance the delivery of holistic care, ensuring that patients receive the necessary referrals and support to address critical needs in the five Health Related Social Needs domains, which include food insecurity, housing instability, transportation, utility challenges, and interpersonal safety.

By Tiffany Ferguson, LMSW, CMAC, ACM

Today I would like to elaborate on recent remarks from Colleen Ejak regarding the 2025 Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) Proposed Rule regarding quality metrics and the inclusion of the social determinants of health (SDoH).

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is expanding its SDoH initiatives for quality reporting from the inpatient setting, where they are currently in the mandatory reporting phase, to the outpatient setting, with a similarly staged rollout. The same measures and processes used in hospitals for inpatients 18 and older are proposed to be incorporated into the Hospital Outpatient Quality Reporting (OQR), Rural Emergency Hospital Quality Reporting (REHQR), and Ambulatory Surgical Center Quality Reporting (ASCQR) programs. Voluntary reporting will begin with the 2025 reporting period, followed by mandatory reporting in the 2026 reporting period/2028 payment or program determination.

Addressing Gaps in Care

CMS acknowledges that patients’ interactions with the healthcare system are often fragmented, and limited by the care setting. For instance, patients receiving care in Hospital Outpatient Departments (HOPDs), Rural Emergency Hospitals (REHs), or Ambulatory Surgical Centers (ASCs) may not have recently accessed care in acute-care hospitals or other facilities where SDoH screenings are already mandated. CMS’s proposed rule highlights that this gap can lead to missed opportunities to identify and address key social risk factors that significantly impact health outcomes. Notably, while the identification of social risk factors is included in this process and reporting, the systematic addressing of these factors is not yet standardized across many HOPDs, REHs, or ASCs.

The expansion of SDoH screening to the outpatient setting aims to align and enhance the delivery of holistic care, ensuring that patients receive the necessary referrals and support to address critical needs in the five Health Related Social Needs domains, which include food insecurity, housing instability, transportation, utility challenges, and interpersonal safety.

Logistical Considerations for Implementation

Similar to the inpatient setting, the SDoH measure in outpatient settings will be calculated based on each outpatient encounter for patients 18 and older. Patients must be offered five specific Health-Related Social Needs (HRSN) domain questions related to personal safety, utilities, housing, transportation, and food insecurity during their care in a HOPD, REH, or ASC. The first measure will evaluate the proportion of patients who are offered the screening tool versus those who actually complete the questions. There are exclusions for those unable to complete or refusing to engage with the screening, which must be appropriately documented. CMS highly recommends that the tool be electronic.

Additionally, the Screen Positive Rate for SDoH measures will report on the percentage of patients who screen positive for one or more HRSNs. This data will be reported separately for each of the five HRSNs, allowing healthcare providers and policymakers to understand the prevalence of specific social risks in different care settings. The data will be reported annually. This will also provide continued data support for Z code capture.

Challenges in Operationalizing SDoH Screening

While this screening tool is a critical step toward addressing the SDoH on a broader scale, there are legitimate concerns regarding how to operationalize this process when a patient screens positive – and determining who will follow up on those needs. Currently, HOPD encounters include lab, imaging, radiology, bedded outpatients, same-day surgery, physician offices, and infusion departments, to name a few. It will be a massive undertaking to determine how these questions will be provided to patients and how appropriate follow-up will be conducted when a patient responds positively to one of them.

To prepare for this rollout, HOPDs, REHs, and ASCs should start discussing the following:

Mechanisms for incorporating SDoH Screening into the registration process: consider integrating these questions into your patient portal to be completed before or at the time of check-in. This will streamline data collection and quality reporting. HOPDs, REHs, and ASCs will need to assess all portals of entry to ensure that these questions are being provided for applicable patient encounters.

Plan for escalation and triage: develop a process for responding to positive SDoH screenings. Something we have learned from responding on the inpatient side to numerous positive screens is to include a question that asks if the patient is already receiving assistance for each need. The questionnaire should also include a question as to whether the patient would like to speak to someone further about their response. If the answer is no, follow-up may not be required, and this should be documented as such. If the answer is yes, determine if the issue can be addressed via a phone call at a later date, or if someone should be available to address the need during the visit. Immediate action should be taken for concerns related to personal safety, while issues related to housing, utilities, food, and transportation could be routed to appropriate teams for timely but non-immediate follow-up. This approach could involve partnerships with community organizations, ambulatory care management departments, post-acute resource centers, or telehealth/phone-call outreach services, likely some type of case management outreach support.

This measure represents both a challenge and an opportunity. It challenges clinicians to integrate SDoH screening into routine care processes, ensuring that all patients are assessed for social risks that may impact their health. At the same time, it offers an opportunity to enhance patient care by addressing the root causes of health disparities and expanding Z code capture, which can improve patient care outcomes.

For a listing of definitions associated with the five core HRSN domains, reference:

Expansion of SDoH Codes as CCs

CMS will now reimburse for inadequate housing and housing instability as indicators of increased resource utilization in the acute inpatient hospital setting.

By Tiffany Ferguson, LMSW, CMAC, ACM

As previously reported for the proposed ruling, it was confirmed in the 2025 Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) Final Rule that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is changing the severity level designation for the social determinants of health (SDoH) diagnosis codes denoting inadequate housing and housing instability, from non-complications or comorbidities (non-CCs) to CCs for the 2025 fiscal year (FY).

Consistent with the annual updates to account for changes in resource consumption, treatment patterns, and the clinical characteristics of patients, CMS will now reimburse for inadequate housing and housing instability as indicators of increased resource utilization in the acute inpatient hospital setting.

Inadequate housing is defined as an occupied housing unit that has moderate or severe physical problems, such as plumbing, heating, electricity, or upkeep issues. CMS describes concerns with patients living in inadequate housing by noting that they may be exposed to health and safety risks that impact healthcare services, such as vermin, mold, water leaks, and inadequate heating or cooling systems (see page 250).

The relevant codes include the following:

Z59.10 (Inadequate housing, unspecified);

Z59.11 (Inadequate housing environmental temperature);

Z59.12 (Inadequate housing utilities);

Z59.19 (Other inadequate housing);

Z59.811 (Housing instability, housed, with risk of homelessness);

Z59.812 (Housing instability, housed, homelessness in past 12 months); and

Z59.819 (Housing instability, housed unspecified).

Please see my prior article on the rationale for this decision. I will also mention that the final rule does express notable interest in food insecurity, Z59.41, as a potential conversion to a CC; however, there was not enough data provided on this Z code to justify the conversion.

Instead of repeating that information, I would like to focus on some of the comments that were released in the final rule.

Generally, the public comments were widely supportive for the proposal to change the severity level designation for several ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes related to inadequate housing and housing instability from non-CCs to CCs for FY 2025. This change was seen as crucial for increasing healthcare access for underserved communities and recognizing the interconnectedness of health and social needs. CMS expects that the movement of these codes to CCs will improve data quality by encouraging providers to ask more detailed questions about patients’ housing status.

Despite the support, there were some continued issues raised regarding operational concerns, particularly the current limitation of only 25 diagnoses being captured on electronic claim forms and 19 on paper bills, which I believe was also mentioned in the FY 2024 Final Rule.

The known concern is that documenting SDoH Z codes could lead to overcrowding of other necessary diagnosis codes, potentially impacting payment and quality measures. Suggestions included expanding the number of diagnosis codes that can be reported or creating a separate reporting method for SDoH Z codes. CMS reminded us all again that these comments must be submitted to the National Uniform Billing Committee (NUBC), which maintains the Uniform Billing (UB) 04 data set and form.

Finally, some commenters expressed concern over CMS’s focus on SDoH Z codes, urging a comprehensive analysis of all diagnosis codes in the ICD-10-CM classification to ensure that MS-DRG payments align with the costs of patient care. They encouraged examining other SDoH Z codes related to food insecurity, extreme poverty, and other social factors to determine hospital resource utilization. Concerns were also raised about the challenges in documenting SDoH, including the lack of standard definitions, the need for training, and potential underreporting due to the sensitivity of the information.

CMS has confirmed that if SDoH Z codes are consistently reported on inpatient claims, the impact on resource use data may more adequately reflect what additional resources were expended to address these SDoH circumstances, in terms of requiring clinical evaluation, extended length of hospital stay, increased nursing care or monitoring (or both), and comprehensive discharge planning. CMS went on to say that they will re-examine these severity designations in future rulemaking. Moving forward, continuous dialogue and adjustments will be essential to address the operational challenges and further enhancements needed to impact the burden of resources related to social circumstances in the acute-care setting.

Community-Acquired Pneumonia is Being Over-Diagnosed

The typical chief complaint was shortness of breath, which can herald pneumonia…or an exacerbation of COPD or heart failure.

By Erica Remer, MD, FACEP, CCDS, ACPA-C

I continue to find multiple instances of misdiagnosis and miscoding of respiratory conditions.

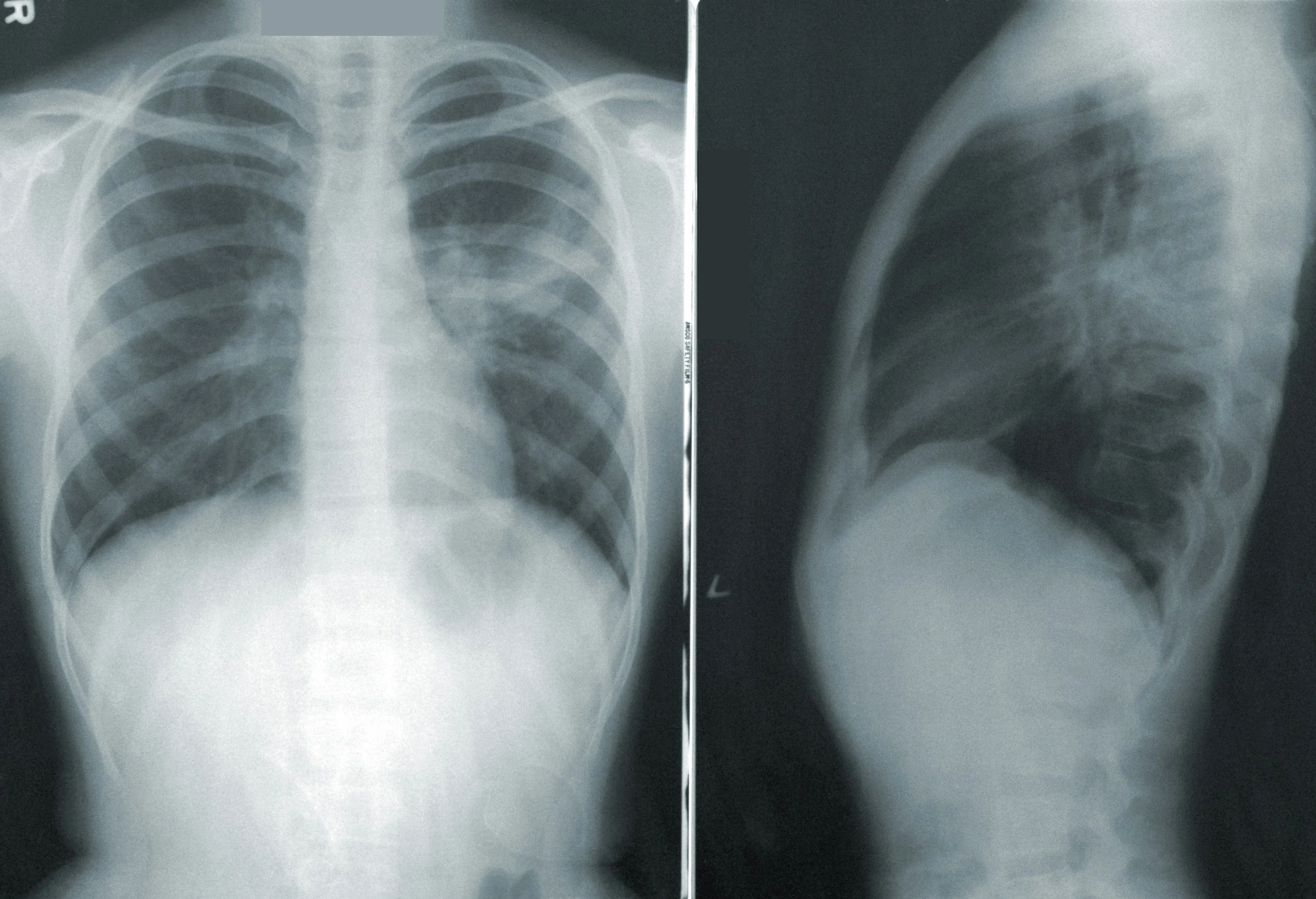

A common scenario was the emergency physician interpreting outside or portable chest X-rays as demonstrating a possible right lower lobe infiltrate indicative of pneumonia, but no additional confirmatory or exclusionary test was performed. Or the emergency physician was the only one who mentioned pneumonia until the clinical documentation integrity specialist elicited subsequent documentation with a query.

Another situation was the patient originally being treated empirically as having pneumonia; it was ultimately not thought to be present, but was never eliminated from the problem list. In retrospect, the patient had some alternate respiratory diagnosis, such as acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or heart failure, but the pneumonia was never declared ruled out in the record.

The typical chief complaint was shortness of breath, which can herald pneumonia…or an exacerbation of COPD or heart failure. What dissuaded me from thinking these patients had pneumonia?

If they didn’t have a fever, a cough (especially productive), or increased respiratory rate, pneumonia seemed less likely to me. If an outside facility’s chest X-ray was not repeated and there was no official radiology overread, if a CT was done and the lung fields were commented on as being clear, or if the pulmonologist did not draw a conclusion of pneumonia on their assessment, I felt the clinical validity was in question.

A recent article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) Internal Medicine validated my impression and sought to characterize the inappropriate diagnosis of pneumonia in hospitalized patients. Authors from a collaborative of hospitals in Michigan asserted that the diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) was inappropriate if the patients had fewer than two signs or symptoms of CAP or negative chest imaging. Signs or symptoms include new or increased cough, change in sputum production, new or increased dyspnea, hypoxemia, abnormal lung sounds, increased respiratory rate, fever or hypothermia, and abnormal white blood cell count. This metric to identify inappropriate diagnosis of CAP has been endorsed by the National Quality Forum.

A total of 17,290 patients were included in the study, and 12 percent were felt to have been inappropriately labeled as having CAP. A total of 88 percent received a full course of antibiotics. Patients who were inappropriately diagnosed with CAP were more likely to be older, suffer from dementia, or present with altered mental status.

Lower respiratory tract infection, including pneumonia, is the most common infectious cause of hospitalization in the United States. It is a common source of sepsis. It is reasonable to empirically treat it if pneumonia is initially a serious concern, but there are perils in not ruling out the condition if it is not actually present. A delay in ruling it out promptly can prevent recognition and appropriate treatment of another condition, which in many cases is really causing the signs and symptoms. Unnecessary antibiotic usage can result in adverse effects, allergic reactions, and development of antibiotic resistance.

The most common presentation was dyspnea and/or cough. Inappropriate diagnosis of CAP was also associated with being on public insurance, having decreased mobility on admission, or having had an inpatient hospitalization within the previous 90 days, in addition to the variables noted earlier. These patients were more often discharged to a skilled nursing facility (SNF).

The study speculated on why physicians might be prone to inaccurately diagnosing CAP. Some of their explanations are that common diagnoses are, well, common, so providers may just settle on the convenient CAP diagnosis; CAP symptoms are also nonspecific and can mimic and overlap with other cardiopulmonary conditions. Moreover, providers are trained to treat early to avoid falling out of historical quality metrics.

What can you do about any of this?

Share this article with your medical providers so they are aware it is a problem.

Perform clinical validation queries, when appropriate

Here are the clinical indicators that should make you suspicious that the respiratory issue is less likely to be pneumonia and more likely to be another condition: no fever, no cough, normal vital signs, normal lung examination, normal white blood cell count;

If there is no reading of imaging other than the emergency provider’s (i.e., no overread by radiology of outside films);

If the radiologist’s read indicates the lungs are clear or states “no infiltrate” or “no pneumonia;”If the diagnosis perpetually remains in an uncertain diagnosis format; and

If the diagnosis perpetually remains in an uncertain diagnosis format; and

If there is conflicting or contradictory provider documentation (e.g., the pulmonologist doesn’t include pneumonia in their impression list).

Reconcile CDI/coder Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) mismatches to ensure that patients with more than one respiratory condition documented end up in the correct DRG.

Your facility may want to set up a task force, system, or quality improvement project to try to reduce misdiagnosis of pneumonia.

Efforts to decrease the incidence of misdiagnosis are not just for clinical documentation integrity; they should improve the quality of care of patients.

And shouldn’t that be our ultimate goal?

What is Chronic Atrial Fibrillation, Anyway?

Using “chronic AF” for all AF could be interpreted as fraud or abuse, an attempt to capture a CC when it isn’t warranted.

By Erica Remer, MD, FACEP, CCDS, ACPA-C

The American College of Physician Advisors’ CDI Committee (disclosure: I am Chair) has published materials on numerous CDI topics. Each set of materials consists of a document detailing the points that a physician advisor should be aware of enabling them to educate their medical colleagues, and another downloadable document of a CDI tip for dissemination to the medical staff with pointers aimed at the clinician.

We are currently revising the tip on atrial fibrillation and flutter, and I found some interesting updates for you.

In 2023, the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association published clinical practice guidelines on the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation (link to article here). For our and my committee’s purposes, the important update was the definitions of the types of atrial fibrillation (AF).

AF is the most common sustained dysrhythmia, which is characterized by disorganized, chaotic wiggling of the upper chamber/s of the heart causing irregularly conducted beats in the ventricles. It is clinically significant because patients seek medical attention, and it is associated with increased risk of stroke, heart failure, and death.

Paroxysmal AF terminates within 7 days or less of onset. It usually does not require intervention. It often is recurrent and intermittent.

Persistent AF is atrial fibrillation which is continuous and lasts for at least 7 days. It requires intervention to convert to normal sinus rhythm. It may recur. The article recommends that if a patient starts off with persistent AF, they should continue to be characterized as persistent even if the pattern of the AF subsequently becomes intermittent and “paroxysmal.”

Long-standing persistent AF is persistent AF that lasts for more than 12 months. The patient and provider have not yet given up the hope that someday this patient may be converted into normal sinus rhythm.

Permanent AF is persistent AF of some duration wherein the provider and patient make a shared decision to abandon efforts to convert the patient into a normal rhythm. There is no inherent difference in the character of the AF; it is just a therapeutic choice. These patients are often given medication long-term to control the rate of their AF and anticoagulation to reduce the risk of stroke or other issues from blood clots.

The new guidelines advise that the expression, “Chronic AF” is historical and should no longer be used. They explain “it has been replaced by the “paroxysmal,” “persistent,” “long-standing persistent,” and “permanent” terminology.” In an American Hospital Association Coding Clinic from 2019, guidance for the diagnostic statement of “chronic persistent atrial fibrillation,” was given that the coder should only use I48.1, the code prior to 2020 for persistent AF because “chronic atrial fibrillation is a nonspecific term” that could be referring to that laundry list of AF.

We’ll come back to this in a few moments.

When revising the materials, we delved deeply into the use of “history of” in the context of AF. As we know, providers and coders have different understandings of what “history of” means. To a coder, it means “old, resolved, in the past, no longer present.” To a provider, it means, “the past medical history includes,” and they do not really make a mental distinction between historical conditions and chronic conditions. The ICD-10-CM code used for verbiage of “history of AF,” Z86.79, is titled Personal history of other diseases of the circulatory system.” Can’t get more vague than that, and it bundles in with “history of” heart failure, coronary artery disease, or aortic aneurysm.

It is disconcerting to a provider to use verbiage indicating a current condition if it is not currently manifesting. This action will require explanation to them. They need to understand that if a patient has had AF in the past and they are still receiving any kind of work-up or treatment for it presently, the patient should be diagnosed with some type of AF. Compare it to diagnosing hypertension in a patient on antihypertensives whose blood pressure is 100/54. They still have hypertension, albeit chronic and controlled, not a “history of.”

On rate control for recurrent short-lived, self-terminating AF = paroxysmal AF. On antiarrhythmic to prevent recurrence of AF which required cardioversion after several months = persistent AF. What if the patient is on anticoagulation for AF, but they are not sure what the duration or type of AF it was, and you can’t access their records? That may be a situation where documenting “chronic AF, type unknown” would be clinically appropriate.